The book “Algeria’s Silence After Civil War” won France’s highest award

Getty Images

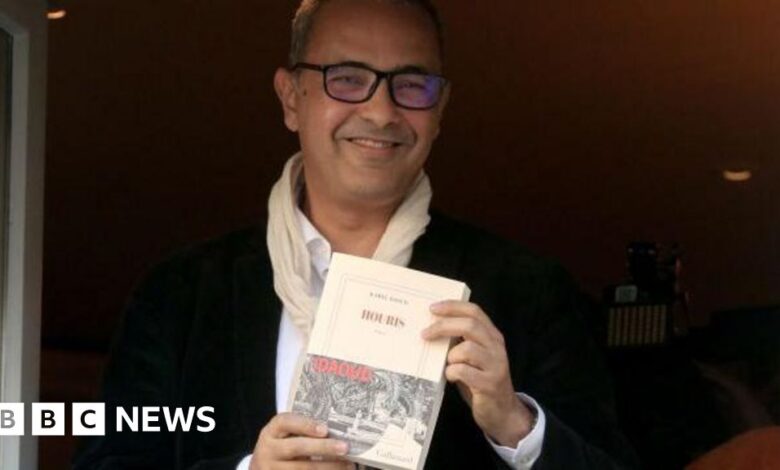

Getty ImagesFor the first time, an Algerian author has won France’s top literary prize, the Prix Goncourt, with his searing account of his country’s 1990s civil war.

Kamel Daoud’s novel Houris is about Algeria bloody “dark decade”.of which an estimated 200,000 people were killed in massacres believed to have been carried out by Muslims or the military.

The female protagonist Fajr (Dawn in Arabic) has survived having her throat slit by Muslim militants – she has a smile-like scar on her neck and needs a speaking tube to communicate – and tells the story. her story for the baby girl she carries inside her.

Written in French, the book “speaks to the suffering of Algeria’s dark times, especially the suffering of women,” Goncourt committee said.

“It shows that literature… can chart another path for memory, besides the historical narrative.”

The irony is that very few people are inside Algeria will likely read it. The book does not have an Algerian publisher; French publisher Gallimard was excluded from the Algiers Book Fair, and news of the success of Daoud’s Goncourt – a day passed – has not yet been reported in the Algerian media.

Worse still, Daoud – who now lives in Paris – could even face criminal charges for talking about the civil war.

The 2005 “reconciliation” law stipulates that acts of “building on the wounds of the national tragedy” are punishable by imprisonment.

According to Daoud, the effect was to make the civil war – which traumatized the entire country – a non-issue.

“My 14-year-old daughter did not believe me when I told her what happened, because war is not taught in school,” Daoud told Le Monde newspaper.

“I cut out some of the worst scenes I wrote. Not because they aren’t true, but because people don’t believe me.”

Daoud, 54, witnessed the massacres firsthand because he was a journalist working for the newspaper Quotidien d’Oran at the time. In interviews, he described the gruesome habit of counting corpses, then seeing his body count altered by the authorities – increasing or decreasing, depending on the message they wanted to give. .

“You develop a routine,” he said. “Come back, write your work and then get drunk.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHe worked as a columnist for many years, but was gradually harassed by the Algerian government for refusing to come forward.

He strongly criticized what he saw as the official “instrumentalization” of the period 1954-1962. war of independence against France; and about what he saw as the continuing subjugation of women in Algerian society.

“In some ways, the Muslims lost the civil war militarily, but they won politically,” he said.

“What I hope is that my book will make people think about the price of freedom, especially for women. And in Algeria, that should encourage people to confront our entire history, not to venerate one part above the rest.”

Daoud has written two previous novels, one of which – the critically acclaimed Meursault Inquiry – is a rewrite of Albert Camus’s The Stranger and was shortlisted for Goncourt in 2015.

In 2020, the author moved to Paris, “exiled by everything” and became a French citizen. “All Algerians are Franco-Algerians,” he said. “Either out of hate or out of love.”

In Algeria, he is a divisive figure. His enemies considered him a traitor who had sold his soul to France, while others recognized him as a literary genius of whom the country should be proud.

In the press conference after the award, Daoud himself said that only when he went to France could he write Houris.

“France gave me the freedom to write. It’s a haven for writers,” he said. “To write you need three things. A table, a chair and a country. I have all three.”