Tata family members became British parliamentarians and fought for India’s freedom

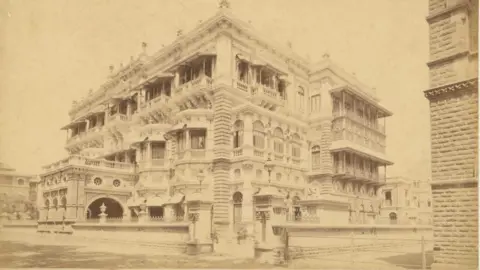

Picryl

PicrylThe name Shapurji Saklatvala may not be one that appears in history books for most people. But like any good story from the past, the son of a cotton merchant – a member of India’s extremely wealthy Tata family – has a pretty good one.

At every turn, it seemed that his life was a constant struggle, challenge and perseverance. He did not share the surnames of his wealthy cousins nor their fates.

Unlike them, he will not continue to run the Tata Group, which is now one of the world’s largest business empires and owns iconic British brands such as Jaguar Land Rover and Tetley Tea.

Instead, he became an outspoken and influential politician who lobbied for India’s freedom in the heart of its colonial empire – the British Parliament – and even clashed with Mahatma Gandhi.

But how did Saklatvala, born into a family of businessmen, pursue a path so different from his relatives? And how did he chart his path to becoming one of Britain’s first Asian MPs? The answer is as complicated as Saklatvala’s relationship with his own family.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesSaklatvala was the son of Dorabji, a cotton merchant, and Jerbai, the youngest daughter of Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, founder of the Tata Group. When Saklatvala was 14 years old, his family moved to Esplanade House in Bombay to live with Jerbai’s older brother (also named Jamsetji) and his family.

Saklatvala’s parents separated when he was young and so young Jamsetji became the main father figure in his life.

Saklatvala’s daughter, Sehri, wrote in The Fifth Commandment, her father’s biography.

But Jamsetji’s fondness for Saklatvala caused his eldest son, Dorab, to resent his cousin.

Sehri writes: “As boys and men, they were always at odds with each other; the rift can never be healed.”

Ultimately, that led to Dorab cutting Saklatvala’s role in the family business, motivating him to pursue a different path.

But beyond family dynamics, Saklatvala was also deeply affected by the devastation caused by the bubonic plague in Bombay in the late 1890s. He saw how the epidemic disproportionately affected the poor and the lower classes. labor, while those in the upper echelons of society, including his family, remained relatively unscathed.

During this time, Saklatvala, a university student, worked closely with Waldemar HaffkineA Russian scientist had to flee the country because of his revolutionary, anti-tsarist political views. Haffkine developed a vaccine to combat the plague and Saklatvala went door to door convincing people to vaccinate themselves.

Sehri writes in the book: “Their views had much in common; and there is no doubt that the close bond between the idealistic older scientist and the compassionate young student certainly helped shape and crystallize Shapurji’s beliefs.”

Getty Images

Getty ImagesAnother important influence was his relationship with Sally Marsh, a waitress whom he married in 1907. Marsh was the fourth of 12 children who lost their father before reaching adulthood. Life for the Marsh family was difficult as everyone had to work hard to make a living.

But the wealthy Saklatvala was drawn towards Marsh and during their courtship he had to face the hardships of the English working class throughout her life. Sehri writes that her father was also influenced by the altruistic lives of the Jesuit priests and nuns he studied under during his school and university years.

So, after Saklatvala arrived in the UK in 1905, he ventured into politics with the aim of helping the poor and disadvantaged. He joined the Labor Party in 1909 and 12 years later the Communist Party. He cared deeply about the rights of the working class in India and Britain, and believed that only socialism – and not any imperialist regime – could alleviate poverty and give People’s voice in governance.

Saklatvala’s speeches were well received and he quickly became a popular figure. In 1922, he was elected to parliament and served as an MP for nearly seven years. During this time, he actively supported India’s freedom. His views were so uncompromising that one British-Indian Conservative MP considered him a dangerous “radical communist”.

During his time as a parliamentarian, he also made trips to India, where he held speeches calling on the working class and young nationalists to assert themselves and pledge their support. freedom movement. He also helped organize and build the Communist Party of India in the areas he visited.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesHis hardline views on communism often clashed with Mahatma Gandhi’s nonviolent approach to defeating their common enemy.

“Dear Comrade Gandhi, we are both capricious enough to allow each other rudeness in order to freely express ourselves correctly,” he wrote in one of his letters to Gandhi, and did not elaborate further. a word about his discomfort with Gandhi’s disapproval. -the movement was active and he allowed people to call him “Mahatma” (a revered person or sage).

Although the two never reached an agreement, they remained cordial to each other and united in their common goal of overthrowing British rule.

Saklatvala’s fiery speeches in India embarrassed British officials and he was banned from returning to the country in 1927. In 1929, he lost his seat in parliament, but he continued to fight for independence of India.

Saklatvala remained an important figure in British politics and the Indian nationalist movement until his death in 1936. He was cremated and his ashes were buried next to his parents and Jamsetji Tata at a cemetery in London – once again uniting him with the Tata family and their legacy.