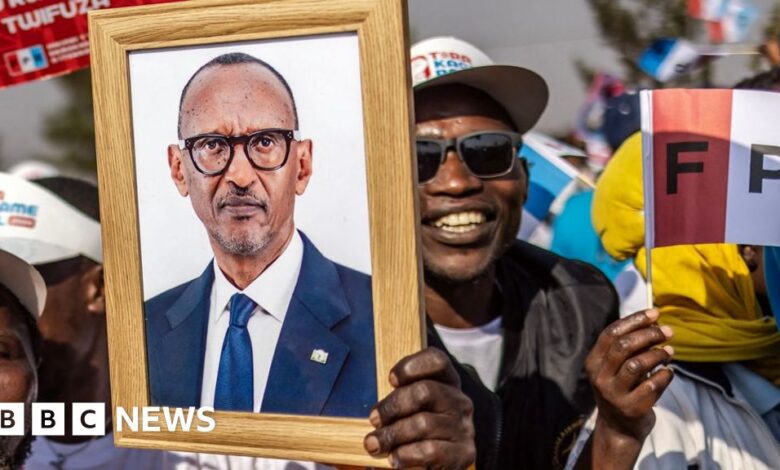

Paul Kagame seeks to extend three decades in power in Rwanda election

Via Didier Bikorimana, BBC Great Lakes Service

AFP

AFPThere is little chance that Rwandan President Paul Kagame will improve on his performance in Monday’s election after winning nearly 99% of the vote in the previous election.

The size of his victory in 2017, along with 95% in 2003 and 93% in 2010, raised some questions about the true democracy of the election.

Criticism that the former rebel and refugee leader confidently denies.

“There are people who say 100 percent is not democracy,” Mr. Kagame told thousands of cheering supporters at a campaign rally in western Rwanda last month.

Referring to elections elsewhere, without naming a specific country, he added: “There are people elected to office with 15%… Is that democracy? How?”

The president stressed that what happens in Rwanda is Rwanda’s business.

His supporters agreed, chanting “they should come and learn” while waving the red, white and blue flags of the ruling Rwanda Patriotic Front (RPF) party.

Standing just over 6ft (1.83m) tall, the lanky 66-year-old father of four cuts a stern and commanding figure in a crowd. He may smile and crack a joke or two, but the bespectacled leader can often grimace like a frustrated old man.

His gentle, penetrating manner of speaking commands the listener’s attention, and when he speaks, he is usually very direct, rarely beating around the bush.

Even when using cryptic or diplomatic language, he used subtext so people would know what he was saying.

AFP

AFPMr Kagame’s life was influenced by the conflict between the Tutsi and Hutu ethnic groups in Rwanda.

To remedy this, his government now requires people to identify themselves as Rwandan rather than any particular ethnic group.

President since 2000, he is running for a fourth term, but Mr Kagame has been the East African nation’s de facto leader since July 1994, when his rebel army overthrew the Hutu extremist government that orchestrated that year’s genocide.

He initially served as vice president and secretary of defense.

Many of his supporters, including some leading Western politicians, credit him with bringing stability and rebuilding Rwanda after the mass killings of 800,000 Tutsis and moderate Hutus.

Some accused his rebel army of revenge killings at the time, but his government has always maintained that these were isolated cases and that those responsible had been punished.

The president has not been slow to criticize the West, but he has also tried to win Western support by sometimes exploiting feelings of guilt over failing to prevent the genocide.

Rwanda was also a partner and financial beneficiary of a now-canceled British programme to send asylum seekers to the country.

“Of course I will vote for PK,” said university student Marie Jeanne, referring to Mr Kagame by his initials.

“Look how well I study. If he wasn’t the president, I probably wouldn’t be able to study because of the lack of security,” she told the BBC.

For her, the answer to the question of who she would vote for was obvious, but there were two other names on the ballot for the nine million registered voters to consider.

Frank Habineza of the Democratic Green Party and Philippe Mpayimana, an independent candidate, are both running for re-election, a repeat of the presidential election seven years ago.

However, last time they received just over 1% of the vote.

Other political parties have backed Mr Kagame for president.

Opposition politician Diane Rwigara, an outspoken critic of Mr Kagame, was barred from running on the grounds that she did not produce valid documents, which she has dismissed as a pretext to prevent her from running.

AFP

AFPMr Kagame has also been accused of silencing other potential opponents through detention and intimidation. He once told the Al Jazeera news channel that he should not be responsible for a weak opposition.

His powerful spy network is believed to have carried out a series of cross-border assassinations and kidnappings.

They have even been accused of targeting their own former boss, former intelligence chief Colonel Patrick Karegeya, who fled Rwanda after falling out with Mr Kagame.

He was murdered in 2014 in his private room at an upscale hotel in South Africa’s main city, Johannesburg.

“They actually used a rope to hang him,” said David Batenga, Colonel Karegeya’s nephew.

Mr Kagame has not appeared to be involved in the killing, while officially denying any involvement.

“You cannot betray Rwanda and get away with it,” he said at a prayer service shortly afterward. “Anyone, even those who are still alive, will suffer the consequences. Anyone. It is just a matter of time.”

The president’s pursuit of domestic security has led him to send troops into the neighbouring Democratic Republic of Congo, saying they were pursuing a Hutu rebel group. Rwanda has also been accused of supporting the M23 rebel group there – something it denies, despite a wealth of evidence, including a recent report by the United Nations.

“To be honest, [the election] “It’s a farce,” said Filip Reyntjens, reflecting on the poll. The Belgian political scientist is an expert on the Great Lakes region.

“Of course I don’t know how it will be this time, but previous elections have been like… a farce.

“I mean the national election commission recorded the votes instead of counting them,” he alleged, citing the 2003 European Union (EU) observer mission report and the 2010 Commonwealth observer mission report.

The Rwanda Electoral Commission states on its website that it conducts “free, fair and transparent elections to promote democracy and good governance in Rwanda”.

“For me, the upcoming presidential election in Rwanda is a non-event,” said Dr. Joseph Sebarenzi, a former speaker of Rwanda’s parliament who lost his parents and many family members in the genocide and now lives in exile in the United States.

“An election is like a football match, where the organizer is also a player, picks the other players, orders everyone to come watch the match, and everyone knows the winner is predetermined but must act as if the match were real.”

Mr Kagame, an avid football fan and follower of Premier League club Arsenal, would reject that description.

AFP

AFPBorn in 1957 into a well-off family in central Rwanda, he was the youngest of five children.

But when he was just two years old, he became a refugee in neighboring Uganda, fleeing persecution and massacres in the late 1950s with his family and thousands of others from the Tutsi minority.

Even though he was just a baby at the time, Mr Kagame said he could still “remember looking out over the hill next door. We could see people burning houses there.

“They were killing people. My mother was so desperate. She didn’t want to leave this place,” the president told American journalist and unofficial biographer Stephen Kinzer.

These killings occurred after Belgian colonists turned to favor an emerging ethnic elite from the majority Hutu ethnic group, some of whom had suffered persecution under the Tutsi monarchy.

Rwanda gained independence in 1962.

In the late 1970s, Mr. Kagame made a series of secret visits back to his homeland.

When in the capital, Kigali, he frequents a particular hotel in Kiyovu, one of the city’s wealthiest neighborhoods. The hotel’s bar is popular with politicians, security guards and civil servants, who often chat over a beer after work.

The future leader would listen to their conversation while sitting alone at a table drinking an orange soda and avoiding attention, Kinzer writes.

These visits to his homeland deepened his interest in the art of espionage.

He trained in military intelligence in Uganda and participated in the successful rebellion in that country led by Yoweri Museveni that came to power in 1986. Mr. Kagame continued his training in Tanzania, Cuba and the United States.

He then led a mainly Tutsi rebel army into Rwanda in 1990.

“[The training] useful. Cuba, in its wars with the United States and its relationship with Russia, has been quite advanced in intelligence matters. There is also political education: What is the struggle about? How to sustain it?” he told Mr. Kinzer.

AFP

AFPHe has sought to sustain the struggle by focusing on economic development – Mr Kagame has argued that Rwanda could follow the example of Singapore or South Korea and achieve development in just one generation.

Although Rwanda has not yet achieved its goal of becoming a middle-income country by 2020, Professor Reyntjens said “it is a well-governed country”.

“The problem in Rwanda is about political governance, there is no level playing field, there is no space for opposition, there is no freedom of speech, [which] risks destroying the achievements of good technocratic governance.”

But Mr Kagame maintains that the huge crowds of supporters at his rallies are just one example of the trust and love the Rwandan people have for him and their desire to continue as their leader, despite his having said he would groom a successor in 2017.

Due to constitutional changes, he could theoretically remain in power into 2034.

“The context of each country matters,” Mr Kagame said in a live interview on state television last month, referring to the issue of his time in power.

“[The West says]: ‘Oh, you’ve been there too long.’ But that’s not your business. That’s the business of the people here.”

Thousands of miles away in the United States, Dr. Sebarenzi said he did not know what the future held for his homeland, affectionately known as the Land of a Thousand Hills, but added: “History shows that in countries where the head of state is stronger than the state institutions, the change of power can be violent, leading to a period of post-regime chaos.”

More BBC stories about Rwanda:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC