Oasis in the Adriatic Sea where Ukrainians and Russians fled the war

BBC

BBC“Our people respect the people of Russia and Ukraine,” Savvo Dobrovic said. “I simply don’t notice any bad relationships.”

It sounds like a recipe for tension and confrontation: tens of thousands of people from opposing sides in a long, bitter war descending on a small Balkan country with only recent memories of conflict their own.

But Montenegro has managed the influx so far.

Since February 2022, Ukrainian refugees and Russian exiles have spread across Europe, fleeing war, conscription, and Vladimir Putin’s rule.

More than four million people have fled Ukraine for temporary protection in the European Union – to Germany, Poland and elsewhere.

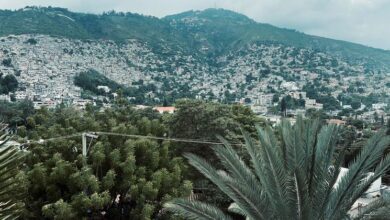

But outside the EU, Montenegro has accepted more than 200,000 Ukrainians, making it the country with the highest number of Ukrainian refugees per capita in the world.

“Montenegrins are very patient,” says Dobrovic, who owns real estate in the Adriatic resort of Budva. They are people who want to help.”

from polo shirtmeaning “slowly”, is an integral part of their lifestyle.

“It surprised me – they were mountain people, but all that remains of that rowdy temperament is looking forward to hugging you.”

Montenegro, a NATO member and candidate for EU status, is not without problems.

The country has a significant Serb population, many of whom are sympathetic to Russia, and six Russian diplomats were expelled two years ago on suspicion of espionage.

But it has won much praise for its response to the refugee crisis – especially its decision granted temporary protection status to Ukrainians, which has now been extended until March 2025.

The most recent figures from September last year showed more than 10,000 people had benefited, and the United Nations said 62,000 Ukrainians had registered for some legal status at that time. That’s almost 10% of Montenegro’s population.

Thousands more have arrived from Russia or Belarus.

For all of these groups, Montenegro is attractive thanks to its visa-free regime, similar language, common religion and Western-leaning government.

That welcome doesn’t always extend to their quality of life.

Although there are plenty of jobs for immigrants in coastal areas, they are often seasonal and poorly paid. Better quality, professional work is harder to find. The luckier ones were able to keep the jobs they had back home, working remotely.

Another difficulty is that it is almost impossible to obtain citizenship here, a problem for those who for whatever reason cannot renew their passports.

There has been a strong Russian presence in Montenegro for many years and it has a reputation, perhaps unfairly, as a playground for the very wealthy.

Many Russians and Ukrainians have property or family ties, but there are also a large number of people who came here almost by chance and felt completely out of place.

For them, the shelter is non-profit Pristaniste (Haven) was established.

Based in Budva, it offers the most desperate people a safe place and a warm welcome for two weeks as they find their footing.

They get help with documents, finding jobs and apartments, and Ukrainians can also come here for two weeks as a “holiday” after the war.

Valentina Ostroglyad, 60, came here with her daughter a year ago from Zaporizhzhia, the regional capital in southeastern Ukraine that is often heavily bombed by Russia.

“When I first came to Montenegro, I couldn’t handle fireworks, even falling roofs – I associated it with those explosions,” she said.

She is currently working as an art teacher and enjoying the hometown where she lives: “Today I went to the stream, watching the mountains and the sea. And people are very kind.”

The ongoing brutality of the war means Ukrainians continue to arrive, no longer able to endure the pain and suffering at home.

Sasha Borkov, a driver from Kharkiv, was separated from his wife and six children, aged 4 to 16, when they left Ukraine in late August.

He was returned to the Polish border – he had previously served time in prison in Hungary for illegally transporting migrants and was banned from entering the EU. His family was allowed to continue on to Germany while he, after several tense days of traveling around Europe, was finally allowed to land in Montenegro.

Clearly stressed and exhausted, he describes how the war finally drove him and his family out of their home.

“When you see and hear every day houses being destroyed, people being killed, it is impossible to convey,” he said.

“Our apartment was not damaged but the windows were broken, and [the bombs] is getting closer and closer.”

Borkov said he had been considering the possibility of going to Montenegro since the start of the war: “[Pristaniste] Take me in, give me food, drink, and shelter. I rested and then started looking for a job.”

He has found a job and his family will join him here. He is applying for temporary protection and a place in a Ukrainian refugee center.

Elsewhere in Budva, Yuliya Matsuy has set up a center for Ukrainian children to learn history, English, math and art – or just to dance, sing and watch movies.

Many people are traumatized by the war, she said: “They don’t care about the mountains or the sea, they don’t want anything.”

“But when they start interacting, their eyes are smiling. The smiles and emotions of those children are impossible to convey. And only then will we understand that we are doing the right thing.”

Now most of it has been resolved. Younger children have learned Montenegrin and are now attending local schools, while older children continue distance learning in Ukrainian schools.

Both charities have Russian volunteers, which has helped foster good relations between the Russian and Ukrainian communities here.

Ruslan Sukhushin/Facebook

Ruslan Sukhushin/FacebookOther parts of Europe also experience occasional friction. At the beginning of the war, Germany noted an increase in attacks on Ukrainians and Russians.

But so far in Montenegro there hasn’t been much like that.

There is a spirit of tolerance here and Pristaniste and its volunteers help promote that.

Sasha Borkov distinguishes between the Russians he met in Budva and those fighting in the war in Ukraine.

“Everyone here is trying to help, they are not doing anything against our country, against us, against my children, [unlike] who bombarded and destroyed our homes and said they were liberating us.”

Friendships have developed between volunteers and residents, as well as among residents, and a Russian-Ukrainian couple living in Pristaniste recently got married.

Empathy is a key factor. A recent talk in Budva by Kyiv-based journalist Olha Musafirova about her work, in Ukrainian, moved Russian audiences to tears, appalled by their country’s actions.

For Ukrainian actress Katarina Sinchillo, the Russian diaspora can be different and Montenegrins are “sensitive”.

“I think the people who live here are a slightly different community because it is the intellectual class, the educated people, the people who cannot live without art,” she said.

Joint Russian-Ukrainian projects are extremely rare.

But Sinchillo founded a theater here, with her husband and co-star Viktor Koshel, using actors from across the former Soviet Union.

“Progressive Russians, who are helping Ukraine, attended with interest and joy,” she said.

Koshel said the environment here is perfect for such contacts. ”Here the countryside is wonderful, it takes you away from urban moods, gloom, depression, political propaganda etc. You go to the sea and all that disappears.”

They have also collaborated with veteran Russian rock musician Mikhail Borzykin, who has witnessed major changes in the Russian diaspora over the past three years.

Before the war, he said, “fierce debates” about Putin among Russians were normal, but the recent influx of anti-war immigrants has created a different atmosphere.

“The vast majority of young people who come here, of course, they understand the horror of what is happening, so there is consensus on the main questions,” he said.

As for the pro-Kremlin former members of Russia’s corrupt elite, whom he called vatnaya migrants, They were sitting quietly in the house they bought in Montenegro many years ago.

“The conflict is not open to the public,” he said.

Borzykin is part of a volleyball team that includes Russians, Belarusians and Ukrainians and says they are “all on the same wavelength”.

Despite the relatively warm welcome, the future of some immigrants remains uncertain.

Strict citizenship laws mean many of them will not be able to stay here indefinitely.

Most Ukrainians seem eager to return home if the war ends because they believe they still have a home to return to.

“There is a big threat to our lives now, but if it ends then of course we will go home,” said Sasha Borkov. “There’s no better place than home.”

But most Russians say it will take more than the regime’s collapse to persuade them to return permanently.

Natalya Sevets-Yermolina, who is from the northern city of Petrozavodsk, said she was in no hurry.

“The problem I have is that it is not Putin who persecutes me, but the little people I live in the same city with,” she said. “Putin is far away but those who follow his orders will stay, even when he is about to die.”

Borzykin said he is also unlikely to make a quick comeback because attitudes can take decades to change.

“Germany needs 30 years [after the Nazis] while a new generation emerges. I’m afraid I won’t have it that long.”

Oleg Pshenichny contributed to this article