Kenyan Botanist Makes Case for Traditional African Medicine

BBC

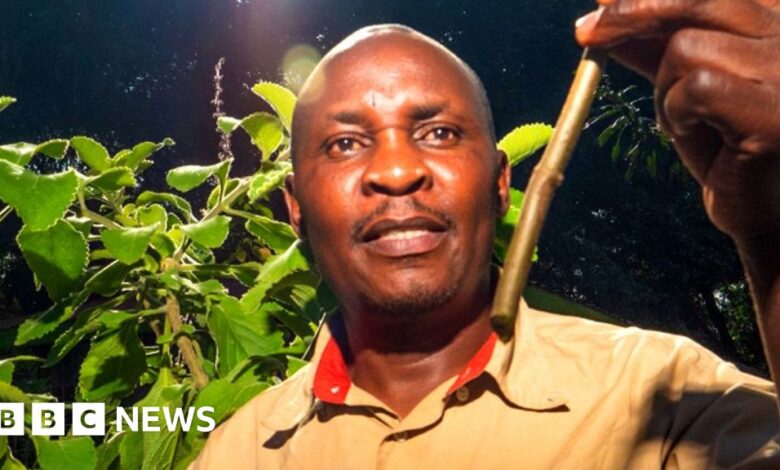

BBCMartin Odhiambo has always been interested in the healing properties of plants – and has been passionate about sharing that knowledge with other Kenyans for many years.

Every Thursday at an outdoor lecture hall at the Nairobi National Museum, he talks to dozens of people who come to learn and exchange information about traditional medicine.

Despite concerns about the effectiveness and safety of these treatments, an estimated 80% of people in African countries use them when they are sick, according to the World Health Organization (WHO).

One way to allay safety concerns in Kenya would be for the government to find ways to monitor traditional medicine, as it has done in some other countries.

But now, Mr Odhiambo wants to share with people the plant-based remedies that he believes can cure common ailments such as colds, skin diseases and stomach aches.

He argues that long before conventional medicine existed, there were healers who knew which methods were effective in treating which conditions.

Information exists in the community but is not really transmitted further.

Mr Odhiambo works for the Indigenous Culture and Health Foundation (Ticah), an organisation that has formed a partnership with the museum, which is seen as a repository of the country’s cultural heritage.

There he maintains a special garden, called the medicinal garden, which has more than 250 species of medicinal plants – they are not for sale but for education.

Over the years, Mr Odhiambo has studied medicinal plants – doing scientific research as well as talking to people who use them – absorbing so much folk and indigenous knowledge that he says he now “tends to dream about plants”.

During a weekly talk on plants, he sounded like an expert as he imparted his vast knowledge to everyone in attendance – including herbalists, a midwife from the US, a psychologist, a teacher, a university student and a businesswoman.

The talk begins with a prayer and a summary of what was learned last week, then quickly moves on to the plants of the day.

The initial focus is Lantana camara – a popular shrub with various local names including “nyabende” and “mukige”.

Traditionally, it is said to cure headaches as well as soothe toothaches – and can act as an insect repellent. Additionally, its branches can be used as toothbrushes.

One participant said it also brought “good energy and created positive energy.”

As the meeting continued, people discussed, shared, and learned about many herbal medicines that treat various health problems.

They also talk about the cultural context in which these plants are used such as in traditional ceremonies, food preservation or even their mystical powers that create “goodwill” in the community.

This forum is not intended to discuss scientific research and whether claims can be proven in a controlled experiment.

“We don’t authenticate this information,” said Vitalis Ochieng, senior program manager at Ticah, emphasizing that the goal is to get people to share what they know.

He added that the organization’s main mission is to highlight the value of traditional medicine and amplify the voices of those who practice it.

One of the obstacles to the widespread adoption of traditional medicine in Kenya is the lack of government policies promoting its safe use.

Indigenous knowledge can be the basis for scientific research, Mr Ochieng argued, adding that in countries like China, traditional medicine is accepted and even exported as “alternative medicine”.

He is campaigning for traditional medicines to be regulated and standardised in Kenya, a law that has been in the works for years.

Today, so-called “herbal clinics”, many of which sell poor quality drugs, have discredited traditional medicine, experts in the East African country admit.

Dr Ruth Nyangacha, deputy director of the Centre for Traditional Medicine Research (CTMDR) – a government body that advises the Ministry of Health on traditional medicine – said there had been problems with fraudsters, as well as deliberate or accidental contamination of products.

This is particularly dangerous for patients with chronic conditions, such as diabetes, who often resort to these drugs, partly because of the cost but also because they are more easily available in remote areas, she told the BBC.

During the museum’s first plant talk, businesswoman Joyce Ng’ang’a said she turned to traditional medicine when she found conventional medicine was not helping her condition.

In fact, the medications she was prescribed after being diagnosed with chronic acid reflux eight years ago had side effects that made her forgetful.

Even a trip to India for treatment did not help – which is why she turned to herbal remedies.

“I have never found a reason to go back to them,” she says enthusiastically, referring to the conventional medicine she has now abandoned.

It’s a practice doctors discourage due to safety concerns, but Ms Ng’ang’a said she hopes her experience will help traditional herbal therapies eventually become formalised.

Patrick Mwathi

Patrick MwathiHerbalist Patrick Mwathi attends plant talks almost every week – keen to improve his craft. He has been practicing for decades, learning directly from his father in the 1970s.

He develops and sells herbal products locally — some of which he shares with others at the presentation, including a “herbal tea” whose packaging claims it can help with infertility. It can also “detoxify” and “activate” the kidneys and “cleanse” the liver, he says.

Another product that is said to be effective in treating depression.

Such treatments have not been scientifically proven to be effective, and Ticah encourages herbalists to register and work with authorities to formalize their healing methods.

Mr Mwathi took samples to government labs for chemical analysis – and they passed tests to prove they were effective and harmless.

But the process required to bring a product to market—including standardization and quality control—is lengthy and involves multiple government agencies. Like other traditional practitioners, he doesn’t have the time or money to do that.

Some of the challenges include knowing when the active ingredients in drugs expire – noting that this often comes down to “guessing”, Dr Nyangacha explained.

CTMDR, a unit of the government-run Kenya Medical Research Institute (Kemri), does not have enough funding to approve the herbal medicines it tests for efficacy for conventional use.

But Dr Nyangacha argued there was no reason it couldn’t be done, pointing out that Kemri had developed its own products, including a herbal medicine used to treat genital herpes and a salt used to treat hypertension.

“We have genuine medicines and traditional medicine. [that]I must say it is effective.”

Mr Odhiambo doesn’t need convincing – in fact, he hopes his passion for plants will show Kenyans that common ailments can be cured without question using remedies “just like the old days”.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC