Jeff Hobbs’ ‘Children of the State’ examines the juvenile justice system : NPR

America persistently has highest detention exchange rates in the world. However, juvenile justice presents a brighter picture.

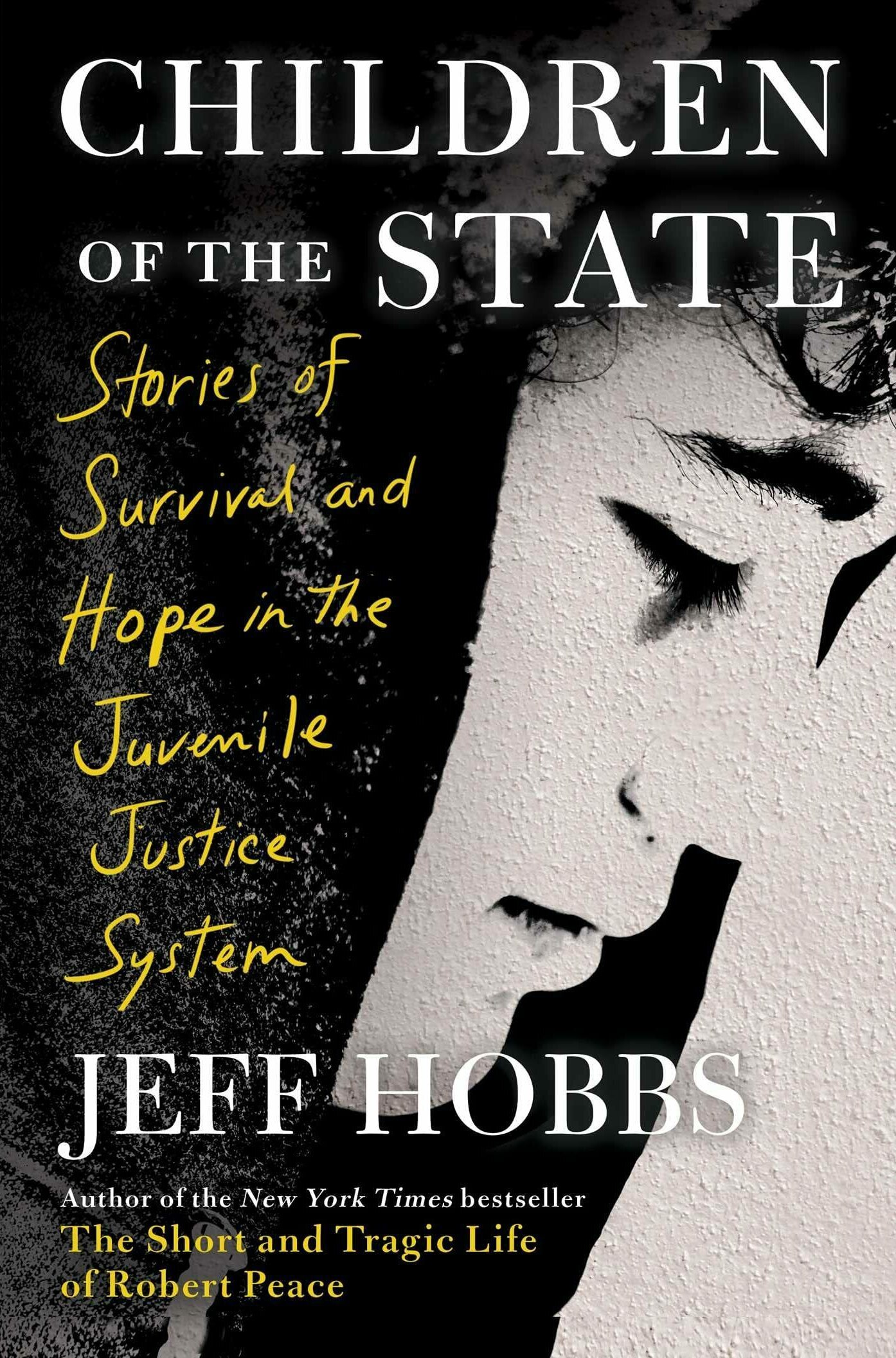

Author Jeff Hobbs’, whose last work The Short Tragic Life of Robert Peace was published to acclaim, wrote a new book examining America’s juvenile justice system.

Children of the State: Stories of Survival and Hope in the Juvenile Justice System provides background information on the evolution of the U.S. juvenile justice system — but mostly about people, not statistics. Many of the statistics are grim and the results sad. “The American penal system is overly punitive, racist, and generally not geared toward recovery,” Hobbs writes.

Most crimes are a matter of state, not federal law. Distributing “justice” is the courts and institutions within a collection of 50 states, the District of Columbia, and numerous sub-governmental entities, such as counties and municipalities. Depending on where the crime is committed, the offender may or may not receive the death penalty, will receive a longer or shorter sentence, etc. Legal definitions of what constitutes a crime vary widely across the United States.

Although it was too late to do so, the Supreme Court banned the execution of minors in 2005. admit “the overwhelming weight of international opinion on the juvenile death penalty.” And the number of young people incarcerated rejected 77% of words 2000 to 2020, according to the US Office of Juvenile Justice and Crime Prevention. These are important steps, but for those who remain incarcerated, the system continues to destroy lives and families, a point well illustrated by Hobbs.

Hobbs tells the story from three points of view. In the first third of the book, titled “Residence,” he follows Josiah Wright, a young black man from Wilmington, who was released from prison after 11 months in custody but eventually had to receive a copy of the book. longer and harsher sentences for violating the amnesty. (Technically, adult prison and juvenile detention. For those behind bars, this can be a segregation without distinction.) Image enhancement. Penalties for pardon violators, even for very minor infractions, help keep America’s incarceration rates high.

Hobbs followed Josiah and his peers to classes, visiting them when they were released, and listening to their opinions. All but a few of these young people are Black or Brown. Some, including Josiah, make stupid and impulsive decisions, like all teenagers. The differences between these children and their “outside” peers tend to be profound childhood traumas and being born into low-income families who are unable to afford them. ability to help shape their children’s lives due to the need to keep food on the table. Wealthier parents, whose children also make the same foolish and impulsive decisions, have access to resources, including time, financial and legal means, as well as connections Social ties tend to keep their children out of the system.

In the middle of the book, “Education,” Hobbs mentions the Woodside Learning Center in San Francisco. “Depression is one of the most common problems in Woodside. Young people thrive on connection but also quickly retreat inside … a space protected with their spirit: walled surrounded, hard, dark, like prison rooms.”

Hobbs focuses on adults tasked with teaching and counseling young people convicted of crimes. Woodside has a lot of dedicated and attentive staff with many years of experience in the system. They also have difficulty balancing the stress of the organization with their home life. They were barely consulted as San Francisco embarked on a massive redesign and reform effort. Woodside is given an end date. Hobbs notes that closing legacy institutions is a goal for many juvenile justice advocates, but that without constructive alternatives, closures could repeat weaknesses. existing in the system.

In the final section of the book, titled “Exile,” Hobbs spends time at Exalt Youth, a New York City agency responsible for helping youth in the juvenile justice system get internships and job placement. do. This is important work, and a small group of young people are drawn into potential careers. But for many of them, it is too difficult to meet the challenges of working in a world that is too foreign to them (read: white and affluent), or they are not prepared academically. art, or their practice makes no sense, or depression and low self-esteem. Beating behavior is too overwhelming.

Throughout, Hobbs lets his characters depict the broken system, rather than writing as an advocate. With admirable research, he does an excellent job of bringing out the humanity of his subjects. Readers care about these people – both adults and young people – and want them to succeed. Sadly, this rarely happens.

Hobbs concluded that America’s youth detention system “is complex, flawed and, above all, inexorably bogged down by generations of rocking, opportunistic, nave, racist ideologies. ethnicity – but now it’s slowly being improved and redesigned, with a deeper concern for the individual.”

Hobbs doesn’t stop there. He writes that “the people in the system, both those tasked with operating its many layers and those who obey its labyrinthine laws – [are] passionate, benevolent, tiresome, admirable and honest. Above all, I see young people being held, even for truly heinous acts, to be able to atone…”

If only redemption were to be the overarching goal of the American penal system.

Martha Anne Toll is a DC-based writer and critic. Her debut novel, three muses, won the Petrichor Prize for Fine Fiction and is published by Regal House Publishing in the fall of 2022.