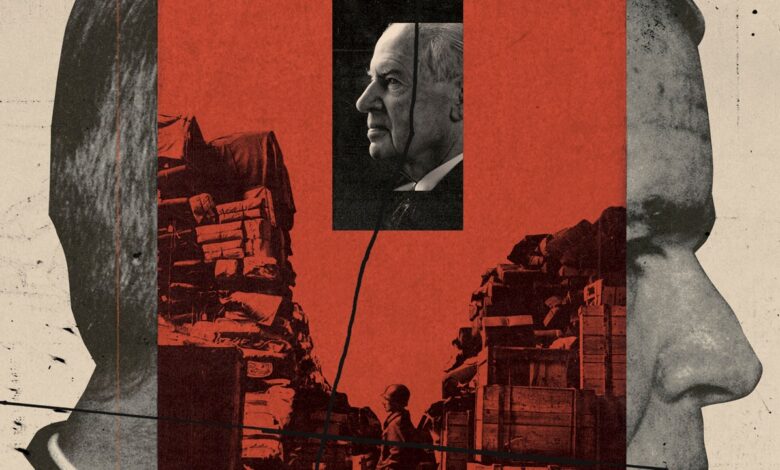

Germany’s richest man is worth $44 billion. Where did his family’s fortune come from? The Nazis knew.

What Kuehne has not explained is why he has not published research that sources say he commissioned.

In early 2014, Kuehne commissioned the Handelsblatt Institute, the independent research arm of the German newspaper Handelsblatt, to conduct a study of the entire history of his family business for the 125th anniversary of Kuehne + Nagel in July 2015. The researchers were even given access to the company’s archives in Hamburg and were assured of academic freedom and independence, according to people familiar with the matter. But when the final results were sent to Kuehne in early 2015, including a chapter on the activities of his father, uncle, and the company during the Third Reich, he refused to publish the study. Kuehne dismissed the study by saying “my father was not a Nazi” during a conference call, according to people familiar with the conversation. When the researchers refused to change the chapter, according to those sources, Kuehne said the study would not be published and ended the call. The 180-page study, which is under contract to Kuehne + Nagel, remains unpublished and inaccessible. Jan Kleibrink, chief executive of the Handelsblatt research institute, would neither confirm nor deny that Kuehne commissioned and shelved the study.

Kuehne declined to be interviewed for this article. Dominique Nadelhofer, a spokesperson for the billionaire, his holding company, his foundation and Kuehne + Nagel, declined to answer detailed questions sent by VF. “Mr. Kuehne was only seven years old at the end of World War II and therefore had nothing to do with the war,” Nadelhofer wrote in an emailed statement. “He is now 87 years old and, once again, these historical events were beyond his control.”

II. THE POLITICS OF MEMORY

For decades of Germany Political leaders have accepted moral responsibility and acknowledged the sins of Germany’s Nazi past, focusing on remembrance as a part of German society. But recently, the country has seemed to be retreating. As the last witnesses to the Nazi era die and cultural memories of the Third Reich fade, the increasingly mainstream right has attacked Germany’s progressive ideals. For much of 2023, the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) polled as the largest party, reaching an all-time high of 23 percent in polls in December. In June 2024, the AfD won a record number of votes in the European parliamentary elections. The party won 16 percent of the German vote and finished second in the election as concerns about immigration and the economy fueled voter discontent.

“Hitler and the Nazis are just a speck of bird droppings in more than a thousand years of successful German history,” then-AfD co-leader Alexander Gauland said in a 2018 speech. The AfD’s extremist wing has been linked to anti-Semitism, Islamophobia and historical revisionism, including downplaying Nazi crimes and downplaying the Holocaust. In May and July 2024, Björn Höcke, a leading AfD politician and founder of the party’s extremist wing, was fined twice by a German court for using the banned Nazi slogan “All for Germany!” in his election campaign speeches. Höcke has lamented the construction of a Holocaust memorial in central Berlin. Calling Germans “the only people in the world to erect a shameful memorial in the heart of their capital,” he called for a “180-degree turn” in the country’s “memory politics.”

Kuehne’s politics can be described as free-market conservative. “I believe that support for the AfD will decline again,” he told the German newspaper Swelling in 2017. “Right-wing movements have no place in Germany.” Since 2021, he has donated about 200,000 euros ($220,000) to the Christian conservative CDU, the party founded by German business and former Chancellor Angela Merkel. Kuehne has even said he could imagine voting for the left-wing Green Party.

But Kuehne’s refusal to publicly reckon with his family and company’s Nazi past has given rise to the revisionist movement, said Henning Bleyl, director of the Heinrich Böll Foundation in Bremen, a research group affiliated with Germany’s Green Party. He has been investigating Kuehne + Nagel’s wartime activities since 2015. These revisionist narratives about Germany’s past are most prominently expressed by the AfD, but the far right in Germany, Austria, France, and many other European countries uses historical revisionism to manipulate the narrative about the Nazi era and World War II to advance their political agenda.

“Even decades ago, Kuehne’s refusal to honestly address his family’s actions during the Nazi period was unacceptable,” Bleyl said in an interview on the terrace above his office in Bremen. “Now it is even more serious because, in my view, Kuehne’s stance places him in the ranks of those who want to ‘whitewash’ German history from its Nazi past.”

III. “A SO-CALLED ARYANIZATION”

Iinterview and new archives unearthed by FOR EXAMPLE in Amsterdam, Bremen, Hamburg, Munich, Montreal, and Washington, D.C., detailing the extent of Nazi profiteering by the Kuehne brothers and their company. Alfred and Werner Kuehne began profiting from the persecution of Jews much earlier than is known: years before World War II and just months after Hitler came to power in Germany on January 30, 1933.

In late April of that year, the Kuehne brothers ousted their Jewish partner and co-owner Adolf Maass after he had spent more than 30 years at the company. Maass, 57 at the time, owned 45 percent of the Hamburg branch of Kuehne + Nagel, which he had founded in 1902 and which was the company’s largest and most profitable division. When Friedrich Nagel died without heirs in 1907, his shares passed to his co-founder, August Kuehne, Alfred and Werner’s father. He died in 1932.

According to a signed and dated contract in the Maass family archives at the Montreal Holocaust Museum, Maass signed over his shares and claims to the Kuehne brothers on April 22, 1933, without compensation. The reason? An alleged inability to “fulfill capital obligations” on the part of the Kuehnes family and the company. Such accusations became a common method in Nazi Germany to remove Jewish shareholders from their own companies. “This was not a free and ordinary business contract,” says Frank Bajohr. “The Kuehnes family took advantage of the political situation for their own benefit. It is no coincidence that this contract was drawn up in the spring of 1933. Maass would not have signed this contract in the years before Hitler came to power. This is called Aryanization.”

“The constitutional element of the Aryanization contract was that Jewish ownership was completely abolished and the company was transferred entirely to non-Jewish owners,” Bajohr said. “In this case, Kuehnes.”

Nine days after Maass’s overthrow, the Kuehne brothers became members of the Nazi Party, according to their de-Nazification records in the Bremen state archives. In the years that followed, the Kuehne brothers developed their company into a “Nazi model company,” an honorary title bestowed on Kuehne + Nagel by the Nazi regime in 1937, the year Klaus-Michael was born. The Kuehne brothers would claim in their de-Nazification proceedings that Maass’s “Jewish origin caused serious trouble” for the company and themselves. The brothers claimed that Maass left voluntarily and that they “did not gain any personal economic benefit from the dissolution of the partnership.”