French village of Mazan devastated by horror as gang rape trial continues

BBC/Léa Guedj

BBC/Léa GuedjA sigh of disappointment echoed through the packed rows of the “Voltaire” courtroom at the Avignon Palace of Justice, as the chief judge, dressed in a red robe, announced the unexpected but inevitable postponement of the trial that had shocked France.

“He is sick,” said Presiding Judge Roger Arata, hinting that this particular case involving 51 accused rapists would be postponed “one, two, three days” or possibly even longer, after it was revealed that Dominique Pelicot was too ill to attend.

His lawyer later said he was taken to hospital.

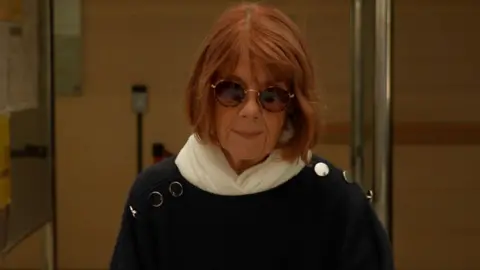

At the right edge of the courtroom, her head gently leaning against the wood-paneled wall, Gisèle Pelicot showed no apparent emotion as she learned that she would not be witnessing her husband testify that day.

Last week, Gisèle Pelicot, 72, told the court that her calm demeanor hid a “devastating scene” from the moment four years ago when a French police officer informed her that her seemingly loving husband had been drugging her for a decade and inviting strangers – more than 80 local men – into the family home and the couple’s bedroom to rape her while he filmed them.

She waived her right to anonymity to highlight the dangers to women of being drugged and sexually assaulted – known as “chemical subjugation”.

It takes just over half an hour to drive – through rolling hills and vineyards that frame the majestic, almost moon-like backdrop of Mont Ventoux – from Avignon to the quaint medieval village of Mazan, briefly famous as the wedding venue of British actress Keira Knightley.

This is where the Pelicot family lives and where Dominique Pelicot films local men he contacted online.

The mood of any place, at any time, is always difficult to summarize.

“Honestly, no one here cares,” said local caterer Evan Tuvignon, leaning against his booth and noting that people were fed up with the whole thing.

But some women told us that not only was the village shocked, but the revelations in court had also caused new tensions in Mazan and surrounding villages.

The names of the accused have recently been widely and illegally shared on social media, and some of the men have complained to the court that they, their families and children are now facing harassment on the streets and at school.

Two local women loading groceries into a car on a narrow street in Mazan said they saw the names and recognized at least three of them.

“You can imagine how stressful it is. You don’t know who to trust on the street. I’m relieved that I’ll be moving out of this village soon,” said Océane Martin, 25.

But next to her, Océane’s mother, Isabelle Liversain, 50, raised a deeper concern.

It has been revealed that while police have identified and arrested 50 men whose images appeared on Dominique Pelicot’s hard drive, another 30 suspects – currently unnamed and unaccounted for – are still at large.

“So we know that 30 of the 80 are still at large. There is tension here because people don’t know if they can trust their neighbours. You wonder – is he one of those 30? What is your neighbour doing behind closed doors?” Caroline Martin said, her voice sharp with frustration.

But Mazan’s 74-year-old mayor, Louis Bonnet, has sought to downplay those tensions, arguing that most of the alleged rapists came from other villages and trying to paint the Pelicot family as outsiders who had not lived here long.

He added that the threats against the accused and their families were predictable.

“If they were involved in these rapes, it is natural that they are targeted. There must be transparency about everything that happened,” he said, condemning the accused and their actions.

In his interview with us, Mr. Bonnet spoke about the case itself and in doing so, he turned to the attitude that has caused outrage in France as well as deep admiration for Gisèle Pelicot’s courage in confronting them.

“People here say ‘no one was killed’. It would be much worse if [Pelicot] killed his wife. But that did not happen in this case,” Mr. Bonnet said.

He then goes on to talk about the experiences of Gisèle Pelicot.

“She will certainly have difficulty getting back on her feet,” he agreed, but said her rape was less worrying than that of another victim in the nearby town of Carpentras, who “was conscious when she was raped… and will suffer long-term, even more severe, physical and mental trauma.”

“When children are involved, or women are killed, it is very serious because there is no way back. In this case, the family will have to rebuild themselves. It will be very difficult. But they are not dead, so they can still do it.”

When I said he was trying to downplay the Pelicot case, he agreed.

“Yes, I am. What happened was very serious. But I would not say that the village should suffer the memory of a crime that goes beyond the limits of what can be considered acceptable,” he said.

His phrasing seemed awkward. He was condemning the case. He did not want his village to be forever disgraced.

But he also appeared to downplay Gisèle Pelicot’s injury.

I objected again. Many women believe this case has exposed specific patterns of male behavior that need to change, I said.

“We can always change our attitudes, and we should. But in reality, there is no magic formula. People who act this way are incomprehensible and should not be excused or understood. But it does exist,” Mr. Bonnet replied.

Inside the Avignon courtroom, some of the defendants—18 of whom are currently in custody—sit in a special glass-walled section watching the proceedings. A white man with scraggly gray hair strokes his bearded chin. Nearby, a younger black man appears to be dozing.

Earlier, dozens of other defendants – who were not in custody – crowded alongside journalists in a long line outside the courtroom.

Most of the men tried to cover their faces with masks, but some did not. A large man shuffled forward on crutches. Someone pulled a green hood down over their faces.

French law provides the accused with some protection from being identified in the media, but Gisèle Pelicot refused her legal right to privacy, instead wanting to become a symbol of defiance for many French women.

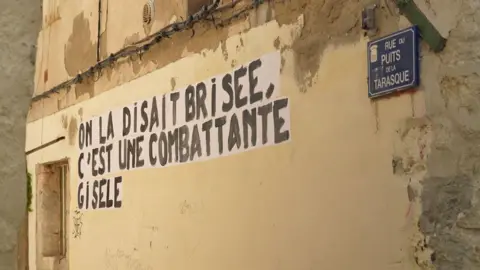

“She showed such dignity, courage and humanity. It was a great gift to [French women] that she chose to tell the world in front of her rapist. They said she was broken. But she was inspiring,” said Blandine Deverlanges, a local activist who attended the trial today.

She and her colleagues recently painted slogans on walls around Avignon. One slogan read: “Ordinary men. Terrible crimes.”

CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFP

CHRISTOPHE SIMON/AFPSitting next to her mother, the couple’s daughter, Caroline, 45, could not hide her emotions.

She was recently given evidence that her father had photographed her without her knowledge or consent. She believes she was also drugged by her father and has become an activist on rape and drugs – an issue that many experts believe is underreported and under-investigated in France.

At times, in court, Caroline would frown or raise her hands to her face in frustration or disgust as various defense attorneys raised objections or argued procedural points. A police officer began presenting evidence, speaking in a thick southern French accent. Bright sunlight streamed through the skylights above the judges.

The atmosphere in the elegantly decorated court was calm, but it was still shocking to see the family – mother, daughter and at least two sons – sitting just metres from the alleged rapists, all of whom had now removed their masks.