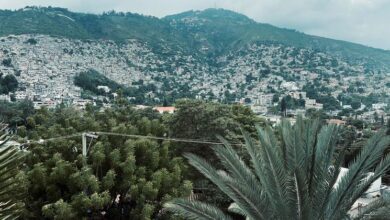

Disabled orphans suffer from China’s ban on overseas adoptions

Aimee Welch

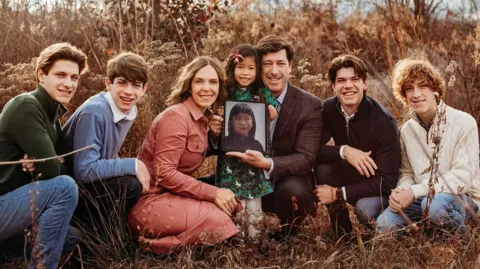

Aimee WelchGrace Welch, 8 years old, has been waiting for her older sister to take the bed next to her since 2019.

Her parents had told her that Penelope, a 10-year-old girl born in China, would join the family living in Kentucky, USA.

Grace, also adopted from China, was born without a left forearm. Her mother, Aimee Welch, said Penelope also has “severe but manageable” special needs, although she doesn’t want to reveal that.

The Welch family, which has four biological sons, sought to adopt disabled children after giving birth to a nephew without arms.

“He taught us all that a person with a limb difference can achieve with the right love and support. His birth started us on the path to adopting Grace,” Mrs. Welch said. “We believe in the dignity and worth of every person, as they are, in all their diversity.”

But the pandemic delayed their plans.

Then in September, China announced that End international adoptionincluding cases where families have been matched with adopted children.

The agonizing wait will especially determine the fate of China’s most vulnerable children – those with special needs.

Updated statistics are not available but Beijing Ministry of Internal Affairs said 95% of international adoptions from 2014 to 2018 involved children with disabilities.

Aimee Welch

Aimee WelchHuang Yanzhong, a senior fellow at the US-based Council on Foreign Relations, said these children “will have no future” without international adoption because they are unlikely to be adopted. domestically adopted children.

Ms. Welch said Grace was especially saddened by the news that Penelope might never return home: “She told me, ‘We were born as a family of eight so everyone could have a friend. ‘”

Ms. Welch called on China to “keep its promises to children who already have adoptive parents.”

Beijing has not commented since the September announcement, when it thanked families for their “love of adopting children from China”. They said the ban was in line with international agreements and showed China’s “overall development and progress”.

The lives of people with disabilities in China

China began allowing international adoptions in 1992 when the country opened up and peaked in the mid-2000s. More than 160,000 children have been adopted by families around the world in three decades via.

The controversial one-child policy has forced families to give up their children, especially girls and children with special needs. Social stigma against disabilities also causes many children with special needs to end up in orphanages.

Dani Nelson, who was adopted to the US in 2017, said she received basic care at an orphanage in the southwestern city of Guiyang, but “it was not enough for me to live a normal life”. live normally”.

The 21-year-old was born with spina bifida – a spinal defect – and hydrocephalus, a neurological disorder that causes water to accumulate around the brain.

During her first three years in America, she had seven surgeries that she said helped her “lead a normal life.”

“I joined a swimming team. I got a job… Adoption saved my life,” said Ms. Nelson, who now works as a cashier at a coffee shop.

Like many Asian societies, people with disabilities in China face discrimination and are sometimes even considered a source of “bad luck.”

China has made some strides in improving access for people with disabilities, but public infrastructure, especially in rural areas, remains weaker than in Western countries. The country has only recently begun to develop educational facilities and curricula for students with special needs.

Only the most severely disabled people receive financial support from the government.

The BBC has previously interviewed Chinese adults with special needs. Parents had to take time off work to take care of their children.

Aware of these challenges, waiting families are concerned about what will happen to the children they intend to adopt, some of whom need urgent medical treatment.

Meghan and David Briggs were matched with a boy in Zhengzhou, Henan, in 2020. The 10-year-old boy had “moderate special needs requiring medical intervention,” Ms. Briggs said.

The couple lives with their 10-year-old biological son in Pennsylvania. Mr. Briggs said the family made a “deliberate choice” to adopt a child who was more vulnerable and less likely to receive specialized care and therapy at a facility in China than with a family in America.

“Such care is a financial and emotional responsibility. We are willing to provide this care because we consider this child as our family,” said Mr. Briggs, who was adopted from Korea.

“He was promised a family by his government,” Ms. Briggs said. “The children are the ones who will bear the brunt of this decision,” she said.

Meghan Briggs

Meghan BriggsA sense of relief for some

Not everyone agrees.

Some people, including adult adoptees, are relieved that Beijing has ended foreign adoptions.

“My experience as a transracial adoptee raised in a predominantly white, Catholic city is that you are often looked down upon. I’m constantly reminded that I don’t belong here,” said Lucy Sheen, who was adopted by a white family in England.

Ms. Sheen, now in her 60s, added that her adoptive family had little knowledge of her Chinese culture and heritage. She was once reprimanded for asking to learn Mandarin.

She added: “Some adoptees have a ‘white savior’ mentality or have an ideology that they will take us where they go because ‘the West is best,’ I think that need to change”.

The Nanchang Project, a nonprofit group that helps connect adoptees with their roots in China, said it felt “relieved that no more children will be separated from their birthplace, culture and their identity”.

“We hope this moment can shift the focus to the need for post-adoption services to support Chinese adoptees and their families,” the group said in a statement last month. for the rest of my life”.

Under the new policy, China will only send children abroad for adoption if the adoptive parents are biological relatives. The BBC understands that the US government is in talks with Beijing about whether more exceptions can be granted to waiting families.

John and Anne Contant, who were matched with 5-year-old Corrine in 2019, said they “respect China’s decision to change its adoption policy.”

“If more families want to adopt domestically, that would be wonderful… Our request is for these 300 children who have been matched [to families in the US] allowed to go home,” he said.

The couple lives in Chicago with their six children. Three of them were adopted from China and live with albinism, as does Corinne.

Contants spoke to Corinne via WeChat when their travel plans to China were shelved because of the pandemic.

“Corinne met our children, saw her house and room prepared for her, and felt the excitement our children felt getting ready,” Mr. Contant said. She was picked up.”

“During one of our conversations, she asked directly: ‘When will you come pick me up?’”