“A Puzzle Should Be Structured Like A Good Joke” – The Influences & Craft Behind ‘Lorelei And The Laser Eyes’

You walk into a poorly lit, seemingly empty hotel. In desperate need of someone to speak to, you hesitantly wander just a single room farther from the entrance, down a serene walkway. You are funnelled into a similarly poorly lit library. You’re second-guessing why you are in this hotel, and why it even has a library, yet your eye is strangely caught by a particular book among the busy shelves.

You let this curiosity afford you a few steps deeper. You reach up a tip-toe’s distance to that possibly glowing book, then hesitantly pull on its spine. You find that it’s heavy. It flops down and you catch it with your other arm. The book, now sprawled open, reveals the following:

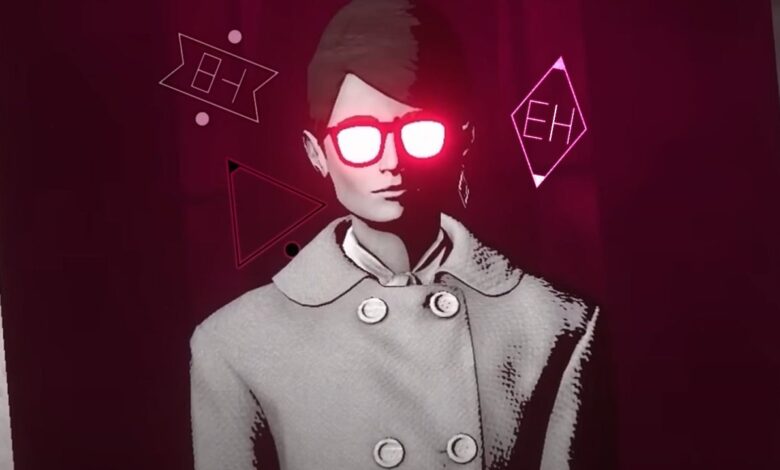

You are playing Lorelei and the Laser Eyes, the latest game from Swedish developer Simogo.

Arriving five long years after their hit Sayonara Wild Hearts, you’d be forgiven if you had no idea it came from the same team; it’s a muted and tense escape room experience much closer to film noir than pop album, yet it’s brimming with the same obsession with the human mind that Simogo is known for over their almost 25-year history.

In an effort to learn more about the many mysteries inside the game and what inspired them, Nintendo Life spoke to Simon Flesser, one half of Simogo’s founding members and a development lead on this Game Of The Year candidate.

Alan Lopez for Nintendo Life: What was your role on Lorelei and the Laser Eyes?

Simon Flesser: I’m Simon Flesser. I made a lot of different things on the project. I was responsible for the overall vision, but also practical things like designing and building the world and its puzzles, writing stories, making textures, effects, placing cameras and such.

I don’t think it’s inaccurate (but feel free to correct me if I’m wrong!) to call Sayonara Wild Hearts Simogo’s biggest commercial success to date. And yet, Lorelei is almost Sayonara’s complete opposite: genre, aesthetic, colours — almost everything. It’s much closer in tone to your previous games, like Device 6.

Did the team have to push through any external friction or internal nerves to follow up a successful action-arcade-musical with a black-and-white puzzle mystery game?

While I don’t have the exact numbers here, [Sayonara Wild Hearts] was certainly the biggest project up to then. But considering how small the team and how short the development time was for things like Device 6, I think one has to consider commercial success relatively. But there’s always some kind of pressure involved in starting a new project. For us, I think the pressure has more to do if we can find something unexpected, different, and surprising enough to make.

I read your development profile on Lorelei, which led me to watch Last Year At Marienbad (1961), a movie you cited as one of the major influences for the game. It struck me how many key things Lorelei infuses from Marienbad, like the hotel setting, the unreliable narration, uncertain characters, visual perspective tricks, and more.

I’m curious…how much was Lorelei’s unrelenting preoccupation with perspective specifically inspired from Marienbad’s writing and cinematography?

The perspective part was mostly a continuation of thought from Sayonara Wild Hearts, actually. [Both games] have, at their core, the idea of trying to ‘solve’ the 3D camera. In some ways, handing over the control of the camera to players is giving up on the idea of solving the camera. So instead of viewing the 3D camera as an issue, we thought about how we instead could make the camera a natural part of the design, and integrate it to create either emotional resonance or gameplay elements. It was from that core idea [that] the idea of perspective as a broader meaning was born.

Interesting. The game definitely explores perspective in all sorts of unique ways, but I didn’t even consider that navigating 3D space has been a relatively new endeavour for Simogo since Sayonara.

I want to ask you about the puzzles…I’m going to be honest with you, Lorelei wasn’t easy for me. And that’s a huge part of what made it one of the most fulfilling games I’ve ever beaten. What was the process for coming up with these types of visual puzzles?

[Puzzle making] is very iterative, and different, depending on the puzzle. As we wanted a large part of the puzzles to be able to be randomised, we had to think about them in very specific ways, which naturally led a lot of them to be based around numbers. We often talked about concepts such as symmetry, consistency, and series.

I thought a lot about how a puzzle should be structured like a good joke, with a good buildup that culminates in a surprising punchline.

The type of puzzles in Lorelei and the Laser Eyes are, to me, largely about communication. It’s about communicating and obfuscating the right amount of information that allows the solver to start having ideas about what the concept of the puzzle is. So typically, I’d test an idea for a puzzle on the team with a sketch, simply asking them to solve them, and then tweak it until it felt like the idea came across. I thought a lot about how a puzzle should be structured like a good joke, with a good buildup that culminates in a surprising punchline.

Without ruining too much, there are some important recurring years in the game. I couldn’t help but wonder if you wrote the story around which particular years you could make the most puzzles out of? Because the mileage the game gets out of some of the number combinations just blew me away. [laughter]

We chose those years for their symbolic value, and for practical puzzle reasons. If I explain the exact practical reason, some puzzles will be given away. But to give an example, no year used in any puzzle has repeating numbers, which was practical for the way we wanted to design puzzles and their randomisation.

I do want to discuss Lorelei’s narrative themes. Gameplay-wise, it’s obviously a box of puzzles, but the puzzles quickly get extended into the characters. Without getting into the story too much, I loved how the game toys with the idea that an observer necessarily changes the context of something. I’d love to hear more about what got you and the team thinking about these themes.

These ideas were formed from our thoughts about entertainment and culture today being so eager to please the audience, rather than trying to create something that feels true…

But if I speak about my thoughts around these themes too much, I’ll project my own meanings onto the players, which I don’t want. I’d like the game to be a vessel for ideas and to raise questions so players can form their own thoughts and views.

To that point, how much do you like to pay attention to the online discourse around the story? Is it ever hard to stay out of it? A casual search around Reddit and Steam forums, and I see a bunch of back and forth regarding people’s interpretations of the story.

We look every now and then. There are plenty of interesting interpretations and analyses. It’s fun to read!

I did find that a puzzle game of this magnitude is surprisingly communal. One of my favourite things to have happened with Lorelei that I didn’t expect was excitement for comparing paper notes with other people who’ve played it. And it was always paper! I can’t show pictures of my notebook because of spoilers, but I love how people instinctively resort to pencil and paper…

We’re big fans of pen and paper ourselves, especially for working. My best ideas come when I am writing and sketching notes, usually on a train.

For anyone who hasn’t played it, a common visual trick the game does is overlay the gameplay on top of strange photographs. It’s subtle, but it was very effective at making me feel uneasy. I read that your team actually took those photographs yourselves…?

That’s right. We travelled to Kronovalls Slott in the southeast of Sweden. We were given the keys by the manager and could roam around all day and take photos.

The castle also has a chapel in one of its wings, but just as we were leaving it, we met the owner in the hallway outside who asked us to not use any photos of the chapel. Perhaps this unintentionally and subconsciously inspired the ‘secret chapel’ in the game.

[Laughter] Also, the music! Simogo’s history with game design around music is fascinating to me, going back to Device 6’s unexpected use of song, the fragmented music in The Sailor’s Dream, to, of course, Sayonara being designed around an original pop album. Lorelei is more muted in this regard, but not without exception.

I’ve always wanted to ask you your opinion on song usage in video games. What compels you to design around, even sometimes sneak fully produced, original pop songs into a game? And do you have any favourite song placements in other video games?

Sound and music is the medium that most easily paints images in my head. We usually make playlists before a project has started, with inspiration from specific songs, albums, era, composer, or even specific instruments. We often produce songs before there is even something playable. For example, both Radio Waves and Laser Eyes were made before we had something playable. Music is often the inception of our ideas, dictating the core of the game.

As for examples in other games, I really like Gusty Garden Galaxy from Super Mario Galaxy. It really amplifies the sense of freedom, adventure and majesty of that level. White Noiz from Silent Hill 2 and its opening is another favourite. It has such strange harmonies, with a really unique mood that is neither scary, nor sad, but still completely sells the entire feeling of the game.

I’m also always a fan of a good credits song that lets you reflect on your experience. Some of my favourites are from Super Mario Bros. 3 (there’s a really great rendition of that song on the album Mario & Zelda Big Band Live), as well as the ending music of Yoshi’s Island.

Personally, I hear a little of that Silent Hill ‘mood uncertainty’ in Lorelei. And don’t get me started on Koji Kondo…what Kondo and Yokota did with Gusty Garden Galaxy in particular is so impressive to me. With Nintendo needing a stunner for the Wii and the prompt ‘Mario IN SPACE!’, it would have been so simple to write the most epic space-opera score of all time. Instead, it’s got this ‘giddy-up’ adventure vibe, almost like an American Western. The restraint and the vision with that score is inspiring. And I still don’t know how the Mario 3 credits score even plays on the NES, it’s so complex! Oh, and as far as good ‘summation’ scores go, I often tell people I want the Staff Roll of Mario 64 played at my funeral…[Laughter]

I’m way off track! Since we’re on the topic of music, I’d love to hear you reflect a little on Sayonara Wild Hearts. It (somehow) just celebrated its five-year anniversary. Looking back, how do you feel today about everything you achieved with that game? Is there anything there you want to return to in the future, or would even do differently?

There are always workflow, technical solutions, and pipeline things that you understand after (or even during) a project that you should have done differently, but I think the released game does what it sets out to do quite well. There’s no specific thing we want to return to or explore more, but we always bring in thoughts and experiences to the next project to make it more enjoyable to work on, and as such Lorelei and the Laser Eyes was a more joyful project for us, even though it has a much more sombre tone.

I’m dying to know…do you know if Queen Latifah ever played the game? [Editor’s note: Queen Latifah voices the narrator.]

I don’t know if Queen Latifah played the game herself, but I was told she watched gameplay before the recording session.

I’d like to think she did, and fixed her broken heart. [laughter] Alright, here’s my last question to you, Simon: Can you solve this puzzle?

No, it’s too tough, I’ll never be able to solve it!

Thank you to Simon for talking to us across the world from his home in Sweden, and outside his native language! This interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Lorelei and the Laser Eyes is out now on Switch (it’s also coming to PS4/5 on 3rd December), and it’s very good.