Witness to the Nakba: A Palestinian teacher is still waiting for a solution 76 years after becoming a refugee in Lebanon

Before the summer of 1948, Mr. Al-Said’s life was like any other child in historic Palestine. Belonging to one of the poorest families in the community, he remembers working to pick olives, climbing trees and playing in the yard with friends.

His father used to cycle to work at a large supermarket chain called Spinney’s in Acre. “We would run out to greet him after work and pull his bike for him,” he said

He recounted his story to UN News’ Ezzat El-Ferri during a visit to his modest home in Al-Bidawi, a large and crowded town in northern Lebanon.

“Our house had only one room. My mother told us to wait for my father to come home. We laid out fruits to eat, cactus fruit, figs, and grapes. All kinds of rain fruits grew on our land,” he said

When the war broke out, his father moved the family to his grandmother’s village a few kilometers from Al-Birwa and returned to defend his homeland. When it became clear that the battle was lost, he returned with his wife and four sons and began the long journey across the Lebanese border.

‘A few days’ turned into 76 years

Mr. Said recalled stopping at several villages along the way, sleeping overnight in olive groves. He recalled a sea of people, “as far as the eye can see” walked in a single file. Each parent carried a small child and a bundle of clothes, while little Mahmoud held a jug of water in his brother’s hand throughout the arduous journey.

“My father told us that we would only be gone for a few days and then return to Palestine. He hoped so,” The family eventually made it to the southern Lebanon town of Jouaiyya, where they rented a room and waited for a day that never came. Sadly, the father suffered a stroke and died just a few months later. “I believe my father died of sadness for his homeland,” he said

After his father died, his uncles convinced his mother to move closer to them, to the northern Lebanese city of Tripoli, where they had just found refuge.

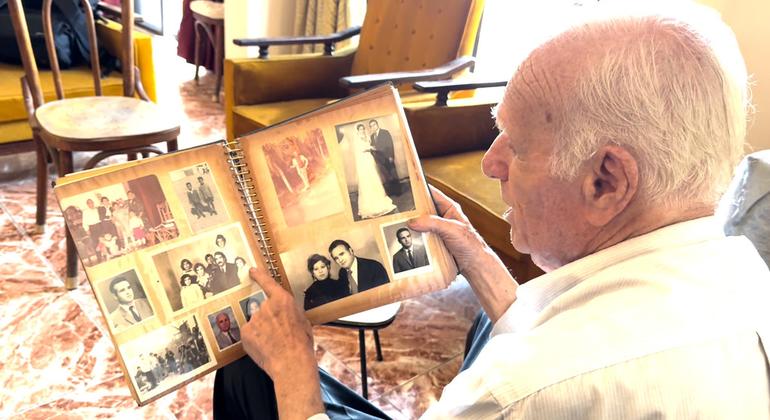

Mahmoud Al-Said holding a photo of him and his brothers taken in 1951.

“My mother used to work in people’s homes in Tripoli. There were no washing machines back then, so she washed their clothes and they would give her a lira or a plate of food. Whenever she got food, she would save it for us in case we couldn’t find anything to eat ourselves. She went through a lot.”

The family lives in a wooden hut near a slaughterhouse in the Tripoli port city of Al-Mina. He said: “The fish would congregate where they sucked blood out to sea, so sometimes we had to go fishing there for a meal.” The family also received assistance from the Red Cross, until that mission was taken over by the UN’s Palestine refugee agency.UNRWA) in 1950.

A child determined to succeed

To help pay for his family, Mahmoud frequented local dumps to search for scrap metal and collected seashells from the shore near their hut to sell. During several summers during his elementary school years, he also worked in a pottery workshop.

Despite learning basic reading, writing and math skills in his village, Mahmoud was still enrolled in first grade at the age of 10. He said many people tried to persuade his mother to put the children in an orphanage and remarry, but she refused and raised them herself.

“People told her that she couldn’t support four children and that she should let us drop out of school and go to work, especially since I was the eldest. She said, ‘How can I let him drop out of school when he already has two degrees (primary and secondary school). At that time, I told my mother to rest and we would go to work to support her.’’

At 19 – when he was 9th level, known in Lebanon as Certificate – Mahmoud was hired to work at a sawmill, packing orange crates, a type of orange that was grown in abundance in Tripoli, known as the city of orange blossoms.

“During Ramadan, my shift would end at 2 p.m. and school would start at 2 p.m. How would I do that? I would dust myself off and go to school in my work clothes. Eventually, I started bringing a change of clothes to work.”

He continued to work there even during his first year of college, then he went to Saudi Arabia on a teaching contract in 1965.

‘Children love people who love them’

Five years later, Mr. Al-Said returned to Lebanon, where he took a job with UNRWA as a part-time teacher. In 1971, he was given a full-time role as a lecturer, beginning a 30-year career of public service.

Mahmoud Al-Said holds a plaque of honor specially made for him and other UNRWA teachers.

He admired his teachers and always dreamed of becoming one. He told us that being a teacher requires passion for the job – he was often the first teacher to arrive at a school and the last to leave – and he stressed that people without that passion should not be in the field.

“I try to be a good example to my students. When they buy me gifts for Teachers’ Day, I tell them that I want nothing more from them than to see them well-behaved and educated. One time an auditor came to me and said, ‘Your students love you.’ I said, ‘Children love people who love them.’

With his witty and cheerful demeanor, Mr. Al-Said has built special relationships with the more than 10,000 students he has taught during his 36-year career.

“I still see many of my first students on the street, and they always give me a warm welcome. Some of them have become UNRWA staff, and some have children and grandchildren – many of whom I also taught. Some of my fondest memories are of being a teacher.”

Like most teachers around the world, he didn’t choose this profession for the money. Teaching at UNRWA schools is a source of pride for him. He says it makes him feel like he’s on the front lines supporting his community. “They are refugees just like us, and if we are not going to sacrifice our lives and money for them, then this is the least we can do,” he explained.

Love of reading

In the 1940s, children like Mahmoud would gather under a tree in Al-Birwa’s courtyard, where a Shiekh – an Islamic scholar – would teach them how to read, write, solve basic math problems and memorize parts of the Quran.

“From the days I was in Palestine and Shiekh first taught me how to read, I loved it. I would pick up any piece of paper with writing or newspaper and try to read it,” he said

Mahmoud Al-Said has been collecting books for 70 years.

Around the age of 14, he developed a new hobby, collecting books and read over a thousand books during his lifetime. “I have amassed a large collection of books over the past 70 years, most of them for free. Many were gifts, and others were thrown away. I will take these books home and restore them.”

A rare case of asylum

Mr. Al-Said, like millions of other Palestinian refugees who are suffering the same fate and are now scattered across Lebanon, Syria and Jordan, has been waiting for a solution to his plight for the past 76 years.

“Leaving Al-Birwa was mandatory because every village that resisted was completely razed to the ground. They left no trace there,” he explained.

“The Palestinian refugee problem is unlike any other the world has ever seen. The uprooting of one people and replacing them with another is unacceptable. It seems unlikely that there will be a solution to this problem anytime soon,” he added.

Mr. Al-Said said the whole Palestinian issue had taken too long to resolve and had “rotten”. He said he had lost hope of returning home but expressed faith in a solution for future generations.

“When I hear the word ‘refugee,’ I feel oppressed. I feel insulted. I feel this should not be happening. Why can’t we address the plight of Palestinian refugees after 76 years?”

He believes the solution should be for the two countries to live side by side under the protection of the United Nations, “so they don’t keep quarreling.”

“There can be no peace between Israelis and Palestinians except through a just solution in which the Palestinian people are given some rights. The majority of Palestinians accept the two-state solution. Negotiations need to be between the two winners. You cannot have real negotiations between the winners and the defeated. Both sides need to feel like they have won.”