Why do some people prefer anti-heroes over superheroes?

Disney

Disney“I may be superman but I am not a hero.”

In Deadpool’s words, he’s “just a bad guy who gets paid” to mess with “worse guys.”

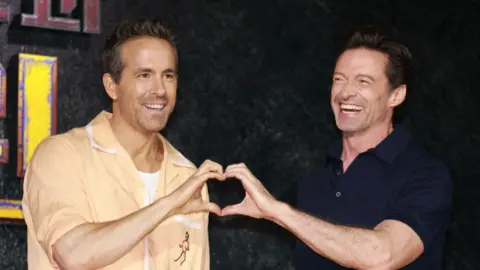

Ryan Reynolds’ character in Deadpool and Wolverine – the third installment of the Marvel franchise out this week – isn’t the only antihero to capture the hearts of fans in recent years.

They are often morally ambiguous characters, neither superheroes nor villains.

Take Wanda Maximoff (Scarlet Witch), who will do anything to create a family, including holding an entire community hostage in the 2021 show WandaVision.

And later this year, the villain Venom will return to the big screen for the third time, as a journalist tries to protect the innocent at all costs.

Deadpool, aka Wade Wilson, gains immortality after participating in an experimental program to cure cancer, but things go wrong and he is left for dead, prompting him to set out on a quest for revenge against those who betrayed him.

But what is it about these murderous and brutal characters that appeal to some people more than superheroes?

beautiful pictures

beautiful picturesAccording to Chelsea-Lee Nolan, a 26-year-old comic book fan from Kent, they are simply “more human”.

“Nobody is completely good or completely bad, so the idea of an anti-hero is quite cool,” she said.

It is in these gray areas that Ms. Nolan can see “elements” of herself.

“I am not perfect and I do not intend to be,” she added. “The idea of a hero who never makes mistakes is incomprehensible.”

For writer and performer Reece Connolly, 30, who lives in London, anti-hero characters are often more realistic.

“They are morally right, but they make mistakes, they have regrets, they have bad habits and personality quirks,” Mr Connolly explains.

In the comic Deadpool (2008), Issue 45, a group of trafficked women call him a “good man” after he rescues them, but the mercenary quickly rejects it, saying, “Okay… well, sometimes there may be parts of me that are good but there are other parts of me that are, well…”

His unwillingness to be called “good” is an admission of his shortcomings.

“The Loud-Mouthed Hijacker,” as Deadpool calls himself, is loud, aggressive, and crazy – everything a superhero is not.

Reece Connolly

Reece ConnollyOther anti-heroes share similar traits. Loki, played by Tom Hiddleston, is a villain who gradually becomes someone who tries to do the right thing, despite his trickster tendencies.

According to Dara Greenwood, of Vassar College in New York, who has spent time studying such characters, the “dark side” that antiheroes embrace plays a huge role in their appeal.

“[They] gives us the imaginative opportunity to explore the “dark side” of human behavior in a safe way without backlash or criticism,” said the associate professor of psychological science.

That may lend some support to the affective bias theory — which holds that entertainment is more enjoyable when a character the audience likes succeeds and an unpopular character fails.

Part of Deadpool’s defining characteristic is his sense of humor. He’s known for his ability to “talk crazy science,” as he calls it, and for his witty one-liners and innuendos — often at the most inopportune times.

When combined with humour, violence can be playful rather than toxic, making us “desensitised” to its brutality, says Professor Greenwood.

Disney

DisneyMany superheroes see their powers as a call to do good — people like Spider-Man remain fan favorites, demonstrating resilience in the face of suffering and continuing to save people rather than harm them.

But Deadpool knows he’s a fictional character who exists for the amusement of others, and he constantly breaks the fourth wall to speak to readers and viewers. A 2019 study found that this relationship gives us the same sense of attachment and intimacy we get in a personal relationship.

Ms Nolan said it made her feel “involved”, while Mr Connolly likened it to “a conversation, or a secret or joke that we are in on”.

For him, anti-heroes like Deadpool are “heroes that still retain all the interesting points.”

“The mess, the weirdness, the flaws,” he said.