Israeli attacks put southern Lebanon hospitals under strain

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay KoraltanWhen the airstrike happened, Mohammed was distributing hot food to elderly neighbors – something he and his friends have been doing since Israel’s latest invasion of Lebanon on October 1.

The civil engineer, 29, was standing about 5 m (16 ft) away from the blast, which destroyed a house in his village in southern Lebanon.

Many layers of skin on his forehead and cheeks were singed, making his face rough and rosy. His hand was burned black. His abdomen suffered third degree burns. Two weeks later, he opened up about his pain and trauma, but wanted to tell his story.

“It’s all black, smoke everywhere,” he said in a low voice. “It takes about a minute. Then I started to realize what was around me. I noticed that my two friends were still alive but bleeding profusely. It took about five minutes for people to get us out.”

Mohammed recounted the horror from his hospital bed at Nabih Berri government hospital, located on a hilltop in Nabatieh. It is one of the largest cities in the south and is only 11km (seven miles) as the crow flies from the border with Israel. Before the war, this was home to about 80,000 people.

Mohammed said there was no warning before the strike – “not at all, not at all to us, not to our neighbors, not to the occupants of the house that was attacked.”

He said the person was a police officer, who was killed in the attack.

“We are not the army, we are not terrorists,” he said. Why are we beaten? The areas attacked were all civilian areas.”

Mohammed will return to his village, Arab Salim, when he is discharged from the army, even though the village is still burning. “I had nowhere else to go,” he said. “If I can [leave] I will. There is no place.”

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay KoraltanAs we toured the hospital, another airstrike sent staff rushing to the balcony to check if anything had been hit this time. The hospital has a panoramic view of billowing gray smoke from high ground about 4km away.

Just then, a few floors above the emergency room, sirens sounded warning of incoming casualties – from that air strike. It attacked Mohammed’s village, Arab Salim.

A woman was carried on a stretcher, blood streaming down her face. She was followed by her husband, who hit the wall in frustration before falling down in shock. The doctors disappeared behind closed doors to examine her.

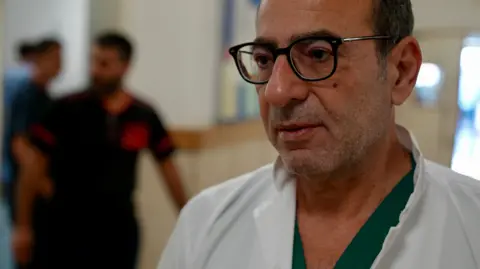

Within minutes, the hospital director, Dr. Hassan Wazni, told staff that her artery had ruptured and had to be transferred to a specialized vascular center at a hospital farther north.

“She needs it immediately,” he said as cries of pain rang out from the clinic. “Talk to Saida [a nearby town]. If possible, take her away now because she can’t wait anymore.”

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay KoraltanThe hospital receives 20-30 casualties from Israeli air strikes every day. Most were civilians, but no one was turned away. “We accept all the patients, all the wounded and all the martyrs here,” he said. “We don’t discriminate between them.”

Dr. Wazni has not left the hospital since the war began. Behind the desk in his office, he opened a pack of cigars. “I think it’s normal to break some rules in war,” he said with an apologetic smile.

He is struggling to pay his salary and earn 1,200 liters of fuel a day to run the generator that powers the hospital. “We received nothing from the government,” he said. “It doesn’t have it.”

His fuel is espresso, which he offers us many times.

With 170 beds, Nabih Berri is the city’s main public hospital but currently has only a core staff and 25 patients. The sick and injured brought here will be quickly transferred to hospitals in safer areas in the North. Employees said there were “many strikes” near Nabih Berri. During our visit there was broken glass inside the lobby.

Nabatieh has been under fire for more than a month.

The municipality building was blown up two weeks ago, killing mayor Ahmad Kahil and 16 others. At that time he was in a meeting to coordinate aid distribution. As we walked past the wreckage, bundles of flat bread were still visible on the floor of a wrecked ambulance.

Reuters

ReutersThe massive strike knocked down several neighboring buildings – a city block missing from the landscape.

Also missing is an Ottoman-era bazaar – the center of Nabatieh – which was destroyed the same day. Centuries of history were crushed into rubble, heritage turned to dust.

The old market, or bazaar, is treasured by Hussein Jaber, 30, a member of the government’s emergency services agency. He and his people, some of whom were volunteers, took us there for a short visit. They drove at high speed – the only way to get around in Nabatieh.

“We were born and raised here,” Hussein said, gesturing toward the surrounding concrete and metal slabs. “We have been here since we were children. The Souk means a lot to us. It’s really sad to see it like this. It holds memories of the past and the beautiful days we spent with the people of this city.”

Like Dr. Wazni, Hussein and his colleagues remained with the people, despite the risks. More than 110 medical workers and first responders have died in Israeli attacks in Lebanon over the past year, according to Lebanese government figures. According to international campaign group Human Rights Watch, some of the attacks involved “clear war crimes.”

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay KoraltanHussein lost a colleague and a friend this month, in an air strike 50 meters from their civil defense station, where they slept with mattresses against the windows. The man who died, Naji Fahes, was 50 years old and had two children.

“He is very enthusiastic, strong and likes to help others,” Hussein told me. “Even though he is older than us, he is the one who rushes into duty, is with the people and rescues them.”

He died, as he lived.

When the airstrike happened, Naji Fahes was standing outside the station, ready to carry out his mission.

As Hussein speaks, we have company. An Israeli drone circled in the sky above then flew lower and noisier. The constant hum of the drone competes with his voice. “We hear it 90 percent of the time,” he said. “We think it’s right above us now. It’s possible it’s watching us.”

For Hezbollah, their presence in the city is out of sight.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) told us that they “operate only against the terrorist organization Hezbollah, not against the Lebanese people.”

Israel says its fight is “against the terrorist organization Hezbollah, located in civilian communities and infrastructure”.

A spokesman said they “took a variety of measures to minimize harm to civilians, including advance warning,” although there was no warning about the airstrike that injured Mohammed or the attack that killed The mayor died.

During our five and a half hours in this once bustling city, we saw two people walking outside. Both quickly left, not wanting to say anything. During our visit, a drone broadcast a message from the Israeli military – instructing people to leave immediately.

It is estimated that there are only a few hundred people left here who are unwilling or unable to move elsewhere. They are mainly the elderly and poor, and they will live and die with their city.

And Hussein and his team will be here to support them. “We are like a safety net for people,” he said. “We will stay and we will continue. We will be with the civilians. Nothing will stop us.”

Additional reporting by Wietske Burema and Angie Mrad