Anger and grief in the nearly deserted southern Lebanese city after the Israeli attack

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay KoraltanConversations in Tire in southern Lebanon are currently taking place in a hurry. It’s unwise to linger on the road and there are fewer and fewer people to talk to.

Conversations can be cut short by the rumble of Israeli bombing or the sound of Hezbollah rocket fire – which can attract incoming fire.

Israeli drones buzz overhead.

You drive fast, but don’t speed up, knowing that there are eyes in the sky. Most likely you are the only car on the empty road – this can make you a target.

That knowledge is always with us, like the armor we wear today.

But civilians here have no armor to protect themselves, and many Lebanese no longer have a roof over their heads. According to Prime Minister Najib Mikati, more than a million people were forced to flee.

Goktay Koraltan

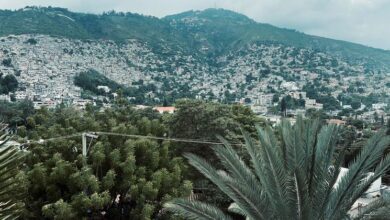

Goktay KoraltanThe war has created a vacuum here – sucking the life out of this ancient city boasting Roman ruins and golden beaches.

The streets are deserted, the shops are closed. The beach is deserted. Windows shake because of Israeli air strikes.

The local civil defense headquarters was abandoned – rescue teams were forced to evacuate – to save themselves after receiving a phone warning from Israel.

The Israeli attacks were getting bigger and closer to our hotel – in recent days several attacks in the hills opposite us appeared to involve some bombs with Israel’s most destructive force, weighing up to 1000 pounds.

And then there is the Hezbollah factor. Even as the armed group is trying to stop the Israeli army from invading Lebanese soil, they are still controlling the international media in the city of Tyre. It limits our movements, although it does not control what we write or broadcast.

In the hospital, doctors looked tired and overwhelmed. Many people no longer go home because traveling is too dangerous.

Instead, they turn to patients like Mariam, 9, whose left leg is in a cast and her arm is heavily bandaged. She lay sleeping in a bed at Hiram Hospital, her dark hair framing her face.

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay Koraltan“She came as a member of a family of nine,” said Dr. Salman Aidibi, CEO of the hospital.

“Five of them have also received treatment. We did Mariam’s surgery and her condition is much better. We hope to bring her home today. Most of the casualties were given first aid here and stabilized before being transferred to other centers, because this hospital is on the front line.”

He said the hospital receives about 30-35 injured women and children every day and this is taking a heavy toll on the staff.

“We need to be positive when we work,” he said. “Remember, that’s when we stop and reflect, that’s when we get emotional.”

When asked about what might lie ahead, his answer was accompanied by a sigh. “We are in a war,” he said. “A destructive war in Lebanon. We hope for peace but we are prepared for every possible situation.”

Also preparing for the worst is Hassan Manna. He remained in Tire as the war tightened. And he’s still in business at the small coffee shop he’s run for the past 14 years. Locals still stop by to chat and reassure with small plastic cups of sweet coffee.

“I will not leave my country,” Hassan told me. “I won’t leave my house. I’m at my place, with my children. I am not afraid of them (the Israelis).

“The whole world is taking to the streets. We don’t want to be humiliated like that.

“Let me die in my house.”

Five of his neighbors were killed in their homes in an Israeli airstrike last weekend. Hassan saw it happen and was thrown into the air by two incoming Israeli missiles.

He tried to walk with only one injured arm.

Goktay Koraltan

Goktay KoraltanAre there Hezbollah targets there? We don’t know. Hassan said those killed were all civilians and members of a family, including two women and a baby.

Israel says its targets are Hezbollah fighters and their facilities, not the Lebanese people. Many people here say otherwise – including doctors and witnesses like Hassan.

Israel says it is taking steps to minimize the risk of harm to civilians – accusing Hezbollah of hiding its infrastructure from civilians.

“There was nothing (no weapons) there,” Hassan insisted. “If there was, we would have left the area. There is nothing to be bombed with. That woman was 75 years old.”

After the strike, he dug in the rubble to find survivors until he collapsed and was taken to the hospital.

When he spoke about his neighbors, his voice cracked with anger and grief — and his eyes filled with tears.

“It’s unfair,” he said, “completely unfair. We know the people. They were born here. I swear I wish I had died with them.”

Ten days ago, we were sightseeing in a Catholic area, near the border.

One local woman – who asked to remain anonymous – told me that people are living in stress.

“The phone kept beeping,” she said. “We can never know when (Israeli) attacks will come. It’s always stressful. Many nights we couldn’t sleep.”

We were interrupted by the sound of an Israeli airstrike, sending smoke rising from the distant hills.

She listed a list of villages near the border – now abandoned and destroyed after a year of tit-for-tat exchanges between Hezbollah and Israel.

She said the damage in these areas was much greater than during the five-week war in 2006. “If people want to go back later, there are no more houses to return to,” she said.

“And there is no home that has not lost a loved one,” she said, “near or far. All men are Hezbollah.”

She told me that before the war, the armed group always “boasted about their weapons and said they would fight Israel forever.” “Privately, even their followers are now shocked at the quality and quantity of Israeli attacks.”

Very few people here dare to predict the future. “We have entered a tunnel,” she said, “and until now we cannot see the light.”

From Tel Aviv, to Tehran, to Washington, no one can be sure what will happen next and what the Middle East will look like the next day.

Additional reporting by Mohamed Madi