Baby penguin miraculously survives iceberg

Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn May, a giant iceberg broke off the Antarctic ice shelf, drifted and stopped – right in front of “perhaps the world’s unluckiest” penguins.

Like a closing door, massive walls of icebergs sealed off the Halley Bay colony from the sea.

It seemed to signal the end for hundreds newly hatched fluffy chicks Their mothers hunting for food may no longer be able to reach them.

Then, a few weeks ago, the iceberg shifted and moved again.

Miraculously, scientists have now discovered that the tenacious penguins have found a way to defeat the giant iceberg – satellite photos seen exclusively by BBC News this week show life in the colony.

But scientists have endured a long, anxious wait until this moment – and the chicks face another deadly challenge in the coming months.

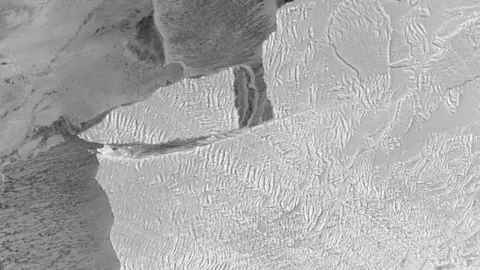

Center for Geographic Information and Mapping BAS/Copernicus Sentinel 2024

Center for Geographic Information and Mapping BAS/Copernicus Sentinel 2024In August, when we asked the British Antarctic Survey whether emperor penguins had survived, they couldn’t tell us.

“We won’t know until the sun comes up,” said scientist Peter Fretwell.

It was still winter in Antarctica, so the satellite couldn’t penetrate complete darkness to photograph the birds.

The title of “perhaps the unluckiest penguins in the world” comes from Peter, who has shared the ups and downs of penguins over the years.

These creatures are on the brink of life and death, and this is just the latest in a series of near misses.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesStruggling between life and death

It was once a stable colony and had 14,000 – 25,000 breeding pairs annually, the second largest in the world.

But in 2019, there was news of a catastrophic breeding failure. Peter and his colleagues discovered that for three years the flock failed to raise any chicks.

Baby penguins need to live on sea ice until they are strong enough to survive in open water. But climate change is warming the oceans and atmosphere, contributing to making sea ice more unstable and prone to sudden melt during storms.

Without sea ice, chicks drown.

A few hundred strays moved their homes to nearby MacDonald Ice Rumples and kept the group going.

That was until iceberg A83, whose 380 square kilometers (145 square miles) is roughly the size of the Isle of Wight, was carved out of the Brunt Ice Shelf in May.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe moment of truth for the chick

Peter feared being completely wiped out. This has happened to other penguin colonies, he explains – an iceberg blocked a penguin colony in the Ross Sea for several years, leading to failed breeding.

A few days ago, the sun rose again in Antarctica. The Sentinel-1 satellites Peter used flew around Halley Bay, taking pictures of the ice sheet.

Peter opened the file. “I was scared when I saw there was nothing there,” he said. However, against all odds, he found what he hoped for – a brown stain on the white ice. The penguins are alive.

BAS/Copernicus

BAS/Copernicus“It was a huge relief,” he said.

But how they survived remains a mystery. The iceberg can be around 15m (49ft) high, meaning the penguins cannot climb it.

“There was a crack in the ice so they were able to dive through it,” he said.

Icebergs can extend more than 50 meters below the waves, he explains, but penguins can dive up to 500 meters deep.

“Even if there’s just a small crack, they can still dive underneath it,” he said.

More danger for the colony awaits

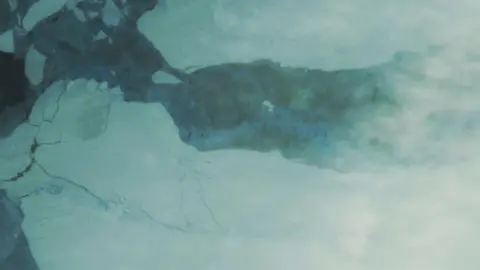

Copernicus Sentinel data is processed by ESA

Copernicus Sentinel data is processed by ESAThe team will now wait for higher resolution photos to show exactly how many penguins are there.

Scientists at the British research facility at Halley will visit to verify the size and health of the colony.

But Antarctica remains a rapidly changing region, affected by our warming planet as well as natural phenomena that make life there difficult.

The MacDonald ice zone where penguins currently live is dynamic and unpredictable, and seasonal sea levels in Antarctica are near record lows.

As the A83 moved, it changed the ice terrain, meaning the penguins’ breeding grounds were now “more exposed”, Peter said.

Cracks have appeared in the ice and the sea’s edge is getting closer.

If the ice breaks under the chicks’ feet before they can swim, around December, Peter warns, they will die.

“They are amazing animals. It’s a bit gloomy. Like many Antarctic animals, they live on sea ice. But it’s changing, and if your environment changes, that’s never good,” he said.