Menendez brothers’ therapist and mistress become the butt of murder trial

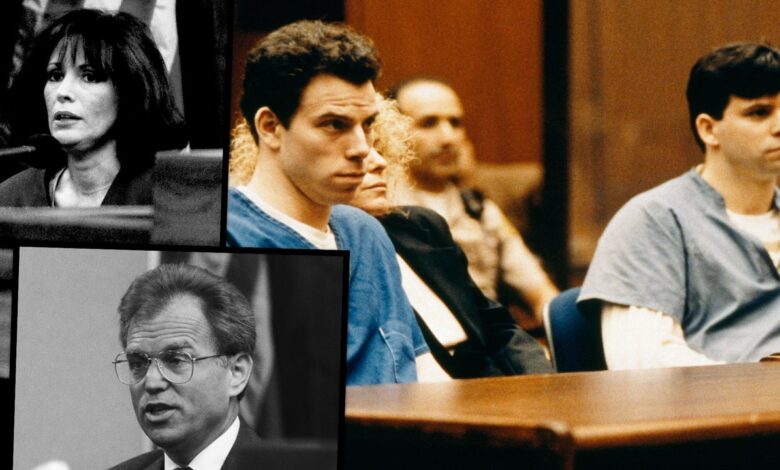

EQUAL Ryan Murphy‘S Monster: The Story of Lyle and Erik Menendez Recalls the Beverly Hills Brothers story in the controversial, real-life glory of the crime camp Lyle And Erik The brutal murder of their parents, José and Mary Louise “Kitty” Menendez, in 1989 is an American horror story. It has all the ingredients to captivate a nation—two pampered, attractive Beverly Hills siblings who make some incredibly stupid decisions (one writes a script about a character who murders his parents; the two spent a combined $700,000 after their parents’ deaths) and allegations of sexual abuse in the country’s most elite zip code. While those ludicrous issues are at the heart of the boys’ Trial in 1993The case also featured two witnesses whose behavior was perhaps equally disturbing (though not criminal): therapist Menendez L. Jerome Oziel and his mistress, Who is Judalon Smyth? Ultimately, the two men temporarily took the court’s attention away from Lyle and Erik. In fact, their testimony became such a farce that no one was invited back to testify at the brothers’ second trial.

Dominick Dunne, who covered the trial for this magazine, credited Erik’s lead defense attorney with Leslie Abramson for taking “a solved first-degree murder case,” complete with confessions from the killers, and transforming it before the public eye. Oziel was the obvious source of evidence in the case: tape recordings of the brothers’ therapy sessions, in which they plot description their parents’ murders (“the perfect crime,” they called it, as Oziel recalls). Abramson fought to have the tapes excluded from the trial. When she lost that battle, she announced that she would discredit the psychologist in “every way known to man and God.”

Throughout the trial, Abramson treated Oziel like a chew toy. She had him Abramson admitted that he failed to tell the Menendez family—who hired him after the children were caught breaking into two homes—that his license was on probation by the state psychology board because of what they called an improper “dual relationship”: trading therapy for construction work done by a patient at his home. request about the 1990 lawsuit Smyth filed against Oziel in Los Angeles Superior Court, alleging that the psychologist had assaulted, raped, kidnapped, and drugged her. When Abramson asked if Oziel had settled the lawsuit for $400,000 to $500,000, he replied that his insurance company had settled. (Oziel also filed a countersuit, alleging that Smyth had developed a “strange obsession and fixation with him.”)

At that time, the state psychological council was accuse Oziel had sex with another woman who worked in his home as a maid—and said he had improperly medicated her and assaulted her. (Oziel denied those allegations.) During the trial, it was also revealed that Oziel had not turned over tapes of his Menendez sessions to authorities. Instead, he had stored the tapes in a safe deposit box and, according to Smyth, had tried to blackmail the brothers by saying that paying him weekly, even if they did not attend the sessions, would help their defense if they went to trial. By the end of Abramson’s long days of criticism, even she was bored, according to Robert Randbook of The Menendez Murders. The lawyer told the judge, during Oziel’s cross-examination the next day, “I’ll be briefer than I thought I would be. Frankly, I’m a little fed up with him.”

Oziel’s testimony was so damaging to his character that, in 1993, LA Times reported that his comfortable life—he had a 6,000-square-foot canyon house, a psychologist wife, two children, and a waiting list for $150-an-hour therapy sessions—was no longer the good life.… For Oziel, his very reputation was on trial.” He faced state disciplinary hearings as a result of the court revelations. In 1997, the Consumer Psychology Board charged Oziel with “various offenses,” according to a Spokesperson who spoke to CNN, including sharing confidential information about his patients with Smyth; having both a business and sexual relationship with Smyth; providing her with drugs; assaulting her twice; and engaging in sexual misconduct with two female clients. (Oziel’s attorney has denied the last allegation, claiming that the women were not patients.) Rather than go to trial, Oziel surrendered his medical license “while simultaneously denying that he engaged in any improper conduct,” according to with his attorney. “He no longer practices psychology and hasn’t for years. It’s not worth the expense and interference in his life.”

The defense’s biggest gift in the first trial may have been Oziel’s mistress: an attractive woman who first contacted Oziel in hopes of relationship therapy. After realizing she couldn’t afford Oziel’s therapy sessions, she had sex with the psychologist, becoming entangled in both his marriage and the Menendez case. After Oziel broke up with her, Smyth told authorities that Oziel had taped confessions from the Menendez brothers.